Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Performance-Based Funding: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Jorge Burmicky*, Allyson T. Clarke, & Charles A. Anderson III

Howard University

Abstract

This paper examined how performance-based funding (PBF) policies shape institutional performance and student outcomes for public four-year or above historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). By conducting a systematic review of the literature, the findings expanded on two main areas, as underscored by the pieces reviewed: (a) how the implementation of PBF policies across states impacts public four-year or above HBCUs, and (b) the intended and unintended consequences of PBF policy on public four-year or above HBCUs. The review of the literature largely indicated that public HBCUs continue to feel the burden of long-term disinvestment and lack of policy planning that is attentive to their histories, mission, and needs. Although researchers are still evaluating the impact of PBF policies on institutional performance and student outcomes based on PBF 2.0, the literature has affirmed that PBF 1.0 has negatively impacted student performance, raising several concerns about the future of HBCUs.

Keywords: HBCUs, performance-based funding, higher education, accountability policies, state policy

* Contact: jorge.burmicky@howard.edu

© 2024 Burmicky et al. This open access article is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Performance-Based Funding: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Despite being heavily scrutinized and chronically underfunded, historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) continue to create access and opportunity for Black students through postsecondary education (Gasman et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2021). National trends indicate that even though most HBCUs have been divested of state and federal appropriations (Boland, 2020; Elliott, 2019; Harris, 2021), they continue to enroll and graduate a disproportionate share of Pell Grant recipient, first-generation, and STEM degree-seeking students (Burmicky et al., 2022; Strayhorn, 2020).

The competitiveness of HBCUs has also been systematically undermined through a series of legislative decisions. For instance, in Maryland, the University System of Maryland (USM) and the Maryland Higher Education Commission (MHEC) have largely ignored the requests from HBCUs for investment in academic programs that could attract and retain students and faculty (Douglas-Gabriel & Wiggins, 2021). This oversight has resulted in diverting Black enrollment from public HBCUs to other schools within the state system that have received more resources. Palmer and colleagues (2011) documented how state systems have played a role in enabling these inequities, such as the case of the MHEC approving the creation of a joint MBA program proposed by Towson University and University of Baltimore, two predominantly White institutions (PWIs), which was opposed by Morgan State University, an HBCU, because of its threat of diverting enrollment from their already existing program.

Originally intended to rectify racial inequities in society, affirmative action partnership initiatives (e.g., faculty/student exchange programs) between PWIs and HBCUs have also served as a mechanism for producing unintended consequences (Cole, 2020; Ortagus et al., 2020). In this paper, we define unintended consequences as the enactment of high-stakes accountability policies that lead to either null, modest, or in some instances negative results when measuring outcomes (Deming & Figlio, 2016). Although intended to set accountability systems to improve conditions for higher education, these policies have not always yielded favorable results to students and their institutions (Hillman & Corral, 2017).

Motivated by President John F. Kennedy’s campaign promises and driven by public and private philanthropy to ameliorate systemic racism in higher education (Cole, 2020), many partnerships and proposals have worked to benefit mostly PWIs in the form of channeling talented HBCU students and faculty into more heavily endowed academic programs. Gasman and Hilton (2012) explained this phenomenon by examining legislative decisions, archival documents, and legal cases to highlight the ways in which White leaders’ commitment to racial justice is only possible when it is also in the interest of White middle- and upper-class communities, also known as interest convergence (Bell, 1992).

Keeping this context in mind, as well as the vital role that HBCUs continue to play in postsecondary education, it is critical to understand how public policy continues to shape educational outcomes. One of the ways in which scholars have studied public policy in higher education is through performance-based funding (PBF) policies. The adoption of PBF policies and models has been prevalent among state officials to allocate state appropriations for higher education (Gándara, 2020). Although scholars and policymakers have begun to scrutinize these funding models, fewer have focused on their impact on racially minoritized populations and minority-serving institutions (MSIs; Gándara & Rutherford, 2018). Furthermore, even fewer scholars and policymakers have focused exclusively on HBCUs (Jones, 2016).

As a result, the purpose of this study is to examine how PBF policy shapes institutional performance and student outcomes for public four-year or above HBCUs (Jones, 2016). By applying a systematic review of the literature as our methodology, our study was guided by the following two research questions upon surveying the literature:

- 1. How has the implementation of PBF policies across several states impacted public four-year or above HBCUs?

- 2. What are the intended and unintended consequences of PBF policies for public four-year or above HBCUs?

To provide context for answering our research questions, we define student outcomes as metrics that have been historically linked to state appropriations through PBF policies, such as “credit hours earned, graduation rates, and educational attainment among historically underrepresented groups” (Ortagus et al., 2020, p. 521; Rosinger et al., 2020). Relatedly, we define institutional performance outcomes as metrics considered by PBF formulas, most frequently the number of students who complete their degree. Yet, in some states institutional performance also includes the number of students retained by the institution, the number of students who accumulated a predetermined number of credit hours, the number of students who graduated in specific high-demand fields, and the average wages of an institution’s graduates (Ortagus et al., 2020). It is important to note that PBF formulas vary depending on the state, and that definitions about institutional performance and student outcomes also vary piece by piece as states define/measure these outcomes differently.

Background

Regardless of the funding mechanism, public HBCUs have faced inequities in state funding for decades, resulting in significant disparities from their non-HBCU counterparts (Williams & Davis, 2019). These disparities vary based on the institution’s mission, Carnegie classification, size, and sector. However, the lawsuit settlement of $577 million between the state of Maryland and its four HBCUs—Bowie State University, Coppin State University, University of Maryland Eastern Shore, and Morgan State University—confirmed the extent to which some public HBCUs have been underfunded and were operating from a disadvantageous position (Douglas-Gabriel & Wiggins, 2021). In the spring of 2021, Governor Larry Hogan signed legislation that provides Maryland HBCUs $577 million over a decade, beginning in the 2023 fiscal year (Douglas-Gabriel & Wiggins, 2021).

To bring some historical context, in his book, the Campus Color Line: College Presidents and the Struggle for Black Freedom, Cole (2020) described the unique tensions that HBCU presidents face while negotiating with state legislators. For example, Cole examined the presidency of Morgan State University, which started as a private university but was then acquired by the State of Maryland and converted into a state-supported institution. By focusing on the leadership of Morgan’s president, Martin D. Jenkins, Cole averred how HBCUs have historically dealt with massive divestment of resources and how they have leveraged the attention of civic, political, and educational policymakers to keep their doors open.

States have funded institutions of higher education using various models based on incremental funding, formula funding, or PBF. The Great Recession negatively impacted state funding and transitioned institutions from being accountable for enrollment to student success metrics such as completion, persistence, research, and work readiness (Lingo et al., 2021). Although PBF is a highly contested topic in higher education, 41 states have used the model to allocate a percentage of total funding, 15 of which are home to public HBCUs. Despite public HBCUs being subjected to discriminatory funding practices, they continue to serve an equity-focused education mission, which has fostered their reputation of having to do more with less (Sav, 2010; Williams & Davis, 2019).

As states grapple with financial instability and shrinking budgets, the shift from funding college costs to college outcomes has widened the revenue chasm between public four-year or above HBCUs and non-HBCUs. A review of Tennessee’s formula profile conducted by the Controller’s Office of Research and Education Accountability (OREA) revealed that Tennessee State University (TSU), the only public HBCU in the state (Tennessee Higher Education Commission, n.d.), had the lowest cumulative change of 8% for the period 2010–11 to 2018–19 in operating funding compared to Austin Peay State University at 52% (Testa, 2018). Furthermore, studies indicate that the demand for institutional accountability is causing states a multitude of unintended consequences. These consequences are exacerbated at HBCUs given that they are underfunded; yet, they remain committed to incurring the additional cost required to educate students who have been historically underserved and navigate barriers to pursue a postsecondary education (Gándara & Rutherford, 2020; Ortagus et al., 2020).

Conceptual Framework

By grounding this study in higher education scholarship and public policy, we applied Ortagus and colleagues’ (2020) systematic synthesis study as a conceptual framework, especially for modeling our research design. In addition, given the various definitions used by PBF policies and their states, we also used this piece to draw on definitions for institutional performance and student outcomes.

In their study, Ortagus and colleagues (2020) conducted a systematic synthesis of the literature on PBF policy, with an emphasis on exploring the intended and unintended consequences of adopting PBF. By drawing from foundational pieces focused on PBF policies, accountability, and student outcomes (e.g., Kelchen, 2018; McDonnell & Elmore, 1987), Ortagus and colleagues provided more context for the meaning of intended and unintended consequences within the realm of public policy. Namely, the authors reiterated that although most PBF policies were designed to “positively influence student outcomes, any policy designed to change an organization’s behavior has the potential to generate both intended and unintended consequences” (p. 524). For example, to respond to PBF policies, institutions may feel the obligation to become more exclusionary, commonly known as more selective (Orphan, 2020), by raising admissions standards to improve educational attainment metrics (e.g., higher graduation and retention rates) imposed by PBF. Such changes have negative effects on historically marginalized student populations, mainly working-class, first generation, students of color. Moreover, it heightens funding disparities for HBCUs, most of which have a historic and contemporary mission of access (Burmicky & McClure, 2021) by providing educational opportunities for Black and African American communities. Other scholars, such as Gándara and Rutherford (2018), have studied the unintended consequences (which in this case, they frame as “unintended impacts”) of PBF policy on underserved populations. Thus, given the rise of research focused on unintended consequences of PBF on historically marginalized populations and sectors, we paid close attention to this phenomenon to frame our research questions.

Like Ortagus and colleagues (2020), we narrowed our search criteria by establishing a series of parameters to further evaluate the impact of PBF policy. For instance, after applying their search criteria, Ortagus and colleagues prioritized pieces of literature with strong casual evidence to understand the causal relationship between PBF implementation and intended and unintended outcomes. By mirroring this approach, we prioritized pieces of literature that investigated funding policies in states with HBCUs that have used PBF. Although we recognize that our selection criterion is considerably narrower in scope compared to Ortagus and colleagues and many other systematic reviews in higher education (e.g., Duran, 2019), we believe in the necessity to conduct an in-depth exploration of these pieces given the historical disinvestment of HBCUs by state and federal agencies (Miller et al., 2021), which is unlike any other educational sector.

Methodology

Guided by Neumann and Gough’s (2020) process for conducting systematic literature reviews, as well as Ortagus and colleagues’ (2020) model for conducting a systematic review of PBF outcomes, we followed distinct yet interconnected methods for designing our study (Burmicky & McClure, 2021). In the first stage, we identified our research questions to narrow down the scope of our review. After identifying the research questions, we developed a selection criterion, which consisted of developing a list of inclusion and exclusion search terms. Given that PBF policies have been adopted by some states approximately 40 years ago since Tennessee first introduced the idea in 1971 (Ortagus et al., 2020), we limited our search to the literature published within the 1971–2022 timeframe. The inclusion terms included a combination of the following: “historically black colleges and universities,” “state funding,” “state appropriations,” “performance-based funding,” “performance funding,” and “outcomes.” We decided on these terms by trying out multiple combinations of various terms associated with public policy, HBCUs, and PBF policy through electronic retrieval databases. In the end, the combination of these terms yielded the most pieces closest to our research questions.

Our search included peer-reviewed journal articles, scholarly books, and book chapters. However, we made exceptions with select working papers if they closely met the parameters of our search. For example, Ortagus et al. (2022) wrote a working paper (which was later published as Ortagus et al., 2023) where they conducted a study that highlighted that HBCUs and other MSIs receive far less per-student state funding than PWIs. This article was important to consider for building on our understanding of PBF policy and its (un)intended outcomes on HBCUs. Because this topic is still relatively new to educational research, we cast a wider net and included doctoral dissertations. Our search targeted mostly empirical studies but remained open to conceptual studies to obtain the full scope of the literature on this topic.

We relied on electronic retrieval databases, including but not limited to Academic Search Primer, ProQuest Central, Ingenta Connect, Social Science Premium Collection, and Gale Academic OneFile. We had access to these databases through the Howard University Libraries (HUL), an HBCU library, which is a part of the Washington Research Library Consortium (WRLC) established in 1987 and comprised of eight research libraries that support universities within and surrounding the Washington, D.C. area (HUL, n.d.).

After employing a combination of the inclusion terms through the advanced search feature of the HUL, we generated a total of 87 results. We reviewed these results one-by-one by looking at the titles and abstracts to ensure that they fit the scope of our research questions. It is important to note that the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) reports that of the 102 HBCUs, 52 are public institutions, 10 of which are two-year HBCUs.

Although public community colleges are also affected by state policy, we excluded this sector in this analysis because some have access to local appropriations, and emphasis was placed on studies that investigated funding policies in the states with HBCUs that have adopted PBF (Ortagus et al., 2020). The literature on state funding policies in Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia was included. These states account for 12 HBCUs that rely on other funding mechanisms. Research on these mechanisms is vital to providing a complete picture of the outcomes and consequences of state policy planning for public four-year or above HBCUs. Although the popularity of PBF has increased in the literature, the review will focus on studies that involve HBCUs. Exceptions were made for studies that included data from states with public four-year or above HBCUs excluding the University of the District of Columbia (UDC) and University of the Virgin Islands or nationwide investigations such as the diffusion of PBF policies conducted by Li (2017). We discussed any pieces that we were unclear about with our three-person research team to make a collective decision. For clarity, we developed Table 1, which shows the pieces of literature that were exclusively focused on HBCUs and PBF, which are very few.

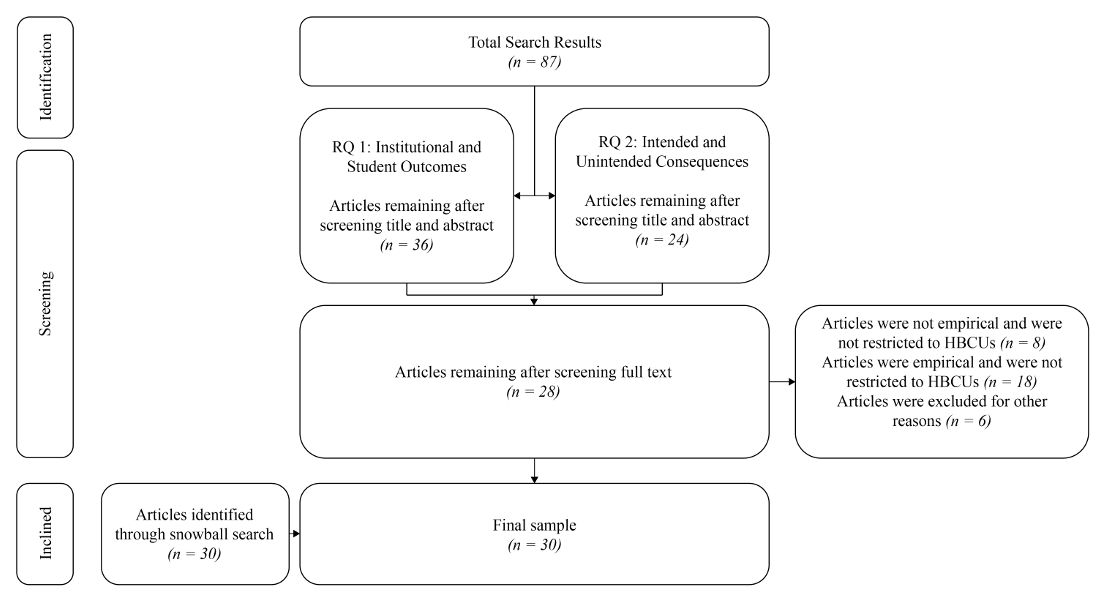

Last, to ensure that we reached saturation and that our search was indeed exhaustive, we engaged in a snowball (or backward) search by examining the reference list of each piece (Duran, 2019). In addition, we relied on Google Scholar to engage in a forward search to look up and examine other pieces that cited our retrieved pieces of literature (Ortagus et al., 2020). After following these careful steps to achieve credibility, our final list of pieces included a total of 30 results (see Table 2 for a full list of all 30 pieces and see Figure 1 for a visual summary of our process). It is important to note that by the time we received the first revision for this paper, two additional pieces related to our topic were published: Ra et al. (2023) and Kelchen et al. (2023). These two papers were not included in our analysis, but we wanted to acknowledge their contribution to the scholarship for future research.

Figure 1. Methodological Process

Analytical Strategy

In the next stage, we developed a matrix to synthesize the literature more efficiently (Goldman & Schmalz, 2004). The matrix method helped us create a spreadsheet that led us to compare, contrast, and merge disparate themes into one coherent whole to provide key takeaways for state-level policy planning for public HBCUs. The matrix was divided into the following categories: title, year of publication, authors, research questions/purpose, methodology, data source, sample population, theory/conceptual framework, findings, and applications to PBF policy. We also created an additional column that indicated which research question each piece was meant to answer.

After reading every piece and filling out our matrix, we used the literature as a form of secondary research (Neuman & Gough, 2020), meaning that we used the content from the primary research to answer our research questions with an eye toward developing implications for public policy that prioritizes HBCUs. To identify patterns in the literature, we relied on an inductive categorization process where we clustered chunks of data from the matrix into themes and patterns (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015). This categorization process was mostly descriptive, meaning that we remained open to comparing and contrasting data from the matrix until we arrived at coherent patterns and themes that best answered our research questions. We used these themes as a part of our findings and as our process for developing public policy implications.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, because of our unique emphasis on HBCUs and public policy, we did not include studies that focus largely on MSIs that did not speak uniquely of HBCUs. We recognize this as a limitation, as legislative discussions about funding HBCUs occur largely under the umbrella of MSIs. Similarly, it is possible that many pieces of scholarship that discuss MSIs include or relate to HBCUs, even though they may not specifically mention it.

Second, our search did not include community college HBCUs. Our decision stemmed from conducting a larger exploration of statewide funding policies versus local appropriations. Although the number of pieces focused on community college HBCUs is extremely small, we recognize that public community colleges, especially HBCUs, are subject to similar legislative issues that their four-year counterparts experience.

Last, as per much of the scholarship on HBCUs, it is possible that any articles published prior to 2008 may have erroneously included predominantly Black institutions (PBIs) as HBCUs in their analysis. Although there is no way for us to confirm this within the pieces of literature we examined, the PBI designation was established under the Higher Education Act in 2008 and is defined as institutions that serve at least 1,000 undergraduate students and enroll at least 40% African American students, among other criteria.

Findings

Research Question 1 (RQ1): The Impact of PBF Policies on Public Four-Year or Above HBCUs

There are numerous studies on PBF. However, there is a paucity of scholarship on its impact on HBCUs, especially when focusing on state appropriations and its impact on institutional performance and student outcomes. The initial search combination to answer RQ1 identified 36 pieces of literature; however, 18 were excluded after carefully following our methodology where the data source did not explicitly reference public four-year or above HBCUs. Although this literature review was not restricted to state funding based on performance metrics, the chosen period of 40 years overlapped with the increasing adoption of PBF. Subsequently, the 18 studies that were evaluated for the review, 12 of which focused on the institutional impact of funding and six on students, addressed the impact of PBF policies on public four-year HBCUs.

Although PBF policies were first implemented in 1979, there is limited scholarship assessing their institutional impact before the 2000s. However, legislators’ need for greater fiscal responsibility for public funds after the Great Recession prompted the rapid transition from enrollment to PBF models and highlighted a gap in the literature. Additionally, it is important to recognize that there are two PBF models that are commonly referred to as PBF 1.0, policies adopted between 1979 and 2001, and PBF 2.0, policies adopted after 2000. Favero and Rutherford (2019) acknowledge that PBF 1.0 policies appropriated regular state funding based on traditional funding formulas with bonuses allocated as a reward when predetermined outcomes were met. In contrast, PBF 2.0 policies eliminated bonuses and connected funding to performance goals such as retention, completion, and graduation rates. This distinction provides a crucial consideration in the literature when examining the methodologies employed to investigate the outcomes of funding policies on HBCUs. In this section, we discuss two findings closely related to RQ1:

- 1. PBF has had a negative impact on HBCU state appropriations and performance metrics set forth by the state.

- 2. PBF formulas often have not considered the institutional mission of HBCUs.

Negative Impact on State Appropriations and Performance Metrics

Though there is an abundance of research on PBF, its impact on HBCUs remains inadequately addressed in the literature. The 12 studies examined to answer RQ1 utilized a variety of methodologies and conceptual frameworks, which strengthened the overall finding that PBF policies do not support the objectives of HBCUs. As Ortagus et al. (2022) stated, “high-dosage PBF policies had a negative effect on state appropriations for four-year HBCUs . . . serving an above-average share of racially minoritized students” (p. 3). PBF policies fall short of adequately serving HBCUs because they do not consider the historical inequities in state funding and often result in exacerbating them (Favero & Rutherford, 2019; Griffin, 2013; Jones, 2016; Ortagus et al., 2022). Jones’ (2016) employment of critical race theory to examine PBF policies at the institutional and state level revealed that these policies do not support addressing equity gaps for institutions serving underserved students such as HBCUs. The gap has narrowed, but non-HBCUs, with selective or exclusionary admission standards, will continue to have an advantage under the current system, which exacerbates funding disparities between HBCUs and non-HBCUs (Sav, 2010).

Research indicates that states have prioritized funding for PWIs—especially those considered flagship institutions—at the detriment of HBCUs (Boland & Gasman, 2014; Hillman & Corral, 2017). Several studies have referenced TSU to highlight the funding gap and disparities in performance metrics compared to the state’s other non-HBCU institutions. Sanford and Hunter (2011) constructed a linear mixed model on these institutions to assess the impact of PBF on institutional incomes, graduation rates, and monetary value tied to retention rates. The overall results suggested that PBF policies did not motivate institutions to change their outcomes. It is important to note that Tennessee increased its allocation of PBF for minoritized students and increased the weight of research and service.

A longitudinal dataset from the IPEDS for the period 1997–2019 confirmed that PBF adoption decreased state appropriations by $1,288.04 per full-time equivalent, which was significantly higher than the average decrease for MSIs of $486.57 (Ortagus et al., 2022). An important observation in the study conducted by Hillman and Corral (2017), which utilized a differences-in-differences (DID) analysis, noted that HBCUs in non-PBF states gained funding in comparison to HBCUs in PBF states where significant funding per student was lost.

A dissertation with a case study approach also examined the impact of state funding through principal agent- and resource-dependent theories contending that the adoption of PBF aligns with the states’ view of higher education as a neoliberal concept (Elliott, 2019). Namely, Elliot asserted that neoliberal approaches to policy redefine power structures within the stakeholder framework by constricting communication between the HBCU and the state. Similarly, Alfred’s (2016) dissertation explored HBCUs expanding their mission to remain open and appeal to a wider audience that allows a shift or diversity in funding from a nonurbanized student body. This concept has been defined in discussing the relevance and value of HBCUs.

To better understand the widespread adoption of PBF, the literature on policy diffusion was reviewed. Most HBCUs are in southern states and have appropriated funding using PBF policies at some time. Therefore, although the sample did not specify HBCUs, the scholarship by Li (2017) and McLendon et al. (2006) both indicated that proximity to a state with PBF policies was not influential on the neighboring state; however, the finding noted a learning effect where policymakers could glean best practices. Therefore, the literature on institutional performance outcomes on public HBCUs has not shown success in frequently used metrics such as degree completion, student retention, and accumulated credit hours. The study by Jones (2016) suggests that policymakers should consider utilizing performance metrics that align to the unique characteristics of HBCUs.

PBF Formulas and HBCU Institutional Mission

The mission of HBCUs is deeply rooted in their history, with its focus on providing broad access to higher education to “prepare young Black [students] to enter the professional workforce” (Albritton, 2012, p. 312). Therefore, HBCUs’ mission is strictly tied to their institutional performance outcomes, especially considering the role they play in society providing upward mobility and career opportunity for African Americans. Although much of the literature on PBF discusses access-related student metrics that have been used to allocate state funding to institutions of higher education, very few pieces have examined racial disparities, particularly toward African Americans, that stem from the exclusionary history of higher education in the United States (Elliott, 2019). These metrics vary from state to state and are driven by internal and external factors. States with PBF policies promote accountability for higher education institutions and student success with increasing prioritization of underrepresented, nontraditional, and underserved students. This is noteworthy because the mission of HBCUs is to precisely serve these student populations. Thus, looking at scholarship assessing the impact of PBF policies on student outcomes is helpful to understand its impact on HBCUs.

Based on the review of the literature on state funding, it determined that despite extensive research being conducted on student outcomes, much of the scholarship does not investigate the impact of PBF on HBCU students. Nationwide studies have relied on quantitative analysis methods using DID and panel regression analyses that appropriately evaluate the effectiveness of PBF policies as a funding mechanism (e.g., Boland, 2020; Favero & Rutherford, 2019; Gándara & Rutherford, 2020; Hagood, 2019; Ortagus et al., 2022; Rutherford & Rabovsky, 2014). Furthermore, a few qualitative studies have investigated student outcomes by analyzing extant scholarship and case studies (Alfred, 2016; Dougherty et al., 2016; Griffin, 2013; Jones, 2016; Li, 2019). Boland (2020) stated, “the null finding of much of the extant studies on performance funding indicates the inefficacy of the theoretical core of pay-for-performance when applied to higher education (p. 666).” However, these studies yield important implications to consider. First, instead of IPEDS, state-based datasets can be used to assess varying PBF funding metrics and outcomes, which could potentially explore their impact on HBCUs. Second, considering the unique institutional characteristics of HBCUs, researchers may benefit from also utilizing qualitative methods to better understand the decision-making process that leads to funding being allocated in a resource constrained environment. Last, the impact of the underpinnings of PBF 2.0 should be examined to determine their appropriateness in funding historically underresourced institutions.

PBF student outcomes are diverse, and the lack of inclusiveness in the design process results in funding formulas and models that compromise the development of meaningful, comparative data. According to Lingo et al. (2021), student outcomes may include retention, degree completion, graduation, debt repayment, and employability metrics. Rutherford and Rabovsky (2014) noted this challenge in a study conducted on 568 bachelor’s degree-granting institutions across 50 states over the period 1993 through 2010, which defined the performance dependent variables as six-year graduation rates, retention rates, and bachelor’s degree production. This period of time assessed PBF 1.0, and it was determined that it had a negative effect on all three dependent variables. The study considered the effect of institutional differences and presented results confirming that HBCU student outcomes were not statistically significant. Rutherford and Rabovsky (2014) stated that “performance funding does not increase student performance” (p. 201).

Hagood (2019) also investigated how PBF policies affect students at 428 public four-year institutions of higher education (IHE) for the period 1986 through 2014. In total, the study included 19 states, 11 of which had four-year and above HBCUs, which prompted its inclusion in the study. However, no controls were established to determine how institutional characteristics affected outcomes. A key finding noted no positive effect for MSIs, which suggests that PBF could be burdensome to these institutions. In acknowledging that there are differences in the designations of MSI, enrollment versus mission, this finding highlighted the purpose of the literature review and connected to an observation of Hillman and Corral (2017), which suggested that an understanding of graduation rates at MSIs and their ecosystems is needed to understand how students are impacted.

The scholarship that addresses the impact on outcomes for HBCU students is modest. Boland (2020) sought to determine the effect on baccalaureate degree attainment and assess whether outcomes differ between PBF 1.0 and 2.0 at HBCUs for the period 2000 through 2014. Boland relied on a longitudinal study of public four-year HBCUs excluding TSU and the UDC. With the exception of Tennessee, the widespread adoption of PBF policies occurred in the 1990s. Therefore, its exclusion reduced the challenge of selecting the pre- and post-timeframes for the DID design analysis. No explanation was provided for the exclusion of the UDC.

Boland’s (2020) analysis accounted for limitations in previous studies that impact HBCUs and utilized a broader set of control variables to formulate a representative design for total completions. Though graduation rate is an important measure for institutional and student outcomes, it does not include part-time, transfer, and returning students, all of whom are largely enrolled at HBCUs. The results indicated that PBF could negatively impact baccalaureate degree production in public bachelor’s degree-granting HBCUs, which aligns with institutional outcomes and previous studies on lower-resourced institutions. Boland’s acknowledgement of the historic underfunding of HBCUs elevates the urgency in understanding the underlying reasons in states adopting funding policies that undermine the vital mission of HBCUs.

To address the underfunding of HBCUs and the inequities in performance metrics under PBF 1.0, some states offer premiums to encourage IHEs to serve underrepresented, nontraditional, and underserved students. Gándara and Rutherford (2018, 2020) added to the scholarship with their evaluation of premiums offered in states for enrolling and graduating students of color and low socioeconomic status. These studies did not identify HBCUs in the sample; however, they were included to understand the conflicting institutional response to premiums. Dougherty et al. (2016) reported that “senior administrators at several colleges and universities reported to us that the premium provided for at-risk student completions had little impact on their institutions’ actions” (p. 183). However, Gándara and Rutherford (2018) observed that institutions that received PBF premiums increased the percentage of students who were Pell Grant eligible but noted a decrease in students who identified as Black or first-generation. Thus, connected to research question 2 (RQ2), which we discuss further, this causes unintended consequences, as HBCUs feel financial pressures unlike their peers. Seeing enrollment declines from students who identify as Black and first-generation is antithetical to the mission of HBCUs. However, HBCUs are positioned to make difficult decisions forced by state policies that are not attuned to their missions and realities.

Our examination of the literature led us to conclude that researchers are still evaluating the impact of PBF policies on student outcomes based on PBF 2.0; however, the literature affirms that PBF 1.0 has negatively impacted student performance (Ortagus et al., 2022; Rutherford & Rabovsky, 2014; Sanford & Hunter, 2011). Understanding that PBF 1.0 has negative effects on institutional and student performance, it is critical for future research related to PBF 2.0 to understand its role in disrupting the cycle of disinvestment toward HBCUs.

Research Question 2 (RQ2): Intended and Unintended Consequences of PBF Policy on HBCUs

To address RQ2, a search was conducted that examined how PBF policy interacted with HBCUs. The search originally returned 24 results; however, many of these sources did not specifically study HBCUs or mention HBCUs and their relationship with PBF. After analyzing which articles did specify HBCUs, either through their explicit mention or through recognizing HBCUs as the only public MSI in the state (e.g., Ohio, Tennessee), there were a total of 14 articles from this search that were applicable to addressing RQ2. It is important to note that some of the articles that were used to answer RQ2 also applied to answering RQ1 in some instances. Thus, when applicable, we refer to select articles again to answer RQ2 in full.

After examining the articles, we observed that there was a recurring theme of “equity” in policymaking concerning PBF application. To broaden our results and ensure that we did not miss any relevant pieces, we ran the same combination of inclusion terms outlined in our methodology, but this time added “equity” to our list of terms. This new search did not produce many new results but yielded three new pieces that were applied to answer RQ2.

Collectively, this scholarly body reflected that many of the metrics that PBF formulas have applied have not worked favorably for HBCUs in regard to funding, resulting in many unintended consequences. Furthermore, as underscored in our findings for RQ1, we found fewer pieces that consider how PBF formulas account for or consider the historical mission of HBCUs. This is worth highlighting because the mission of HBCUs is to provide mass access to postsecondary education to Black and African American communities that have been systematically excluded from the educational pipeline (Strayhorn, 2020). As such, considering how postsecondary educational inequities have been found among African Americans, it should be critical for high-stakes accountability policies to consider institutional missions in their formula decision making as an effort to mitigate for unintended consequences (Rosli & Rossi, 2016; Zerquera & Ziskin, 2020). As highlighted by Rosli and Rossi (2016), alignment between the use of PBF policies and their goal to reward universities’ success should be done through an equity lens that acknowledges that not all institutions were created equal, let alone created under equitable circumstances.

(Un)Intended Consequences: Inequitable Outcomes

Upon implementing these performance-based models, many states have seen modest to no change in institutions achieving their intended outcomes (Hillman & Corral, 2017; Zerquera & Ziskin, 2020). Gasman (2010) asserted that the ways states decide to distribute their funding across universities has long been skewed against HBCUs and other MSIs. PBF policies have had little impact in ameliorating these inequities, and to a degree, they have perpetuated funding gaps between HBCUs and PWIs (Ortagus et al., 2022). According to Zerquera and Ziskin (2020), historically, PBF policies have had an adverse effect on institutions that have broader admission policies and prioritize equity in their teaching (as opposed to research activity), which is the case for most HBCUs (Boland, 2020).

Scholars have found increased evidence that PBF policies disadvantage institutions that recruit and admit large numbers of Black students, as well as students from underserved communities. This shows that although PBF policies are in theory designed to provide accountability for institutions to improve student outcomes, the literature demonstrates how institutions that enroll a higher percentage of Black students tend to receive less money in the form of state appropriations, resulting in an unintended consequence. However, scholars too have argued that these types of policies perpetuate or demonstrate racial biases in public policy implementation (Glaser et al., 2014; Umbricht et al., 2017). For example, while examining funding policies in Tennessee, Hillman and Corral (2017) found that PWIs in the state that enrolled a higher number of Black students received less money than their public peers in the state. Even then, they received more money than the only public HBCU in the state, TSU, demonstrating how public HBCUs sometimes feel the brunt of inadequate public policy implementation.

The disparities in funding reflect noteworthy trends behind the states’ funding actions. According to Jones (2016), although funding for higher education in some states has increased over the last 30 years, funding directed toward HBCUs remained stagnant. Concurrently, in the years when higher education funding experienced downward trends, HBCU funding decreased at a sharper rate than that of their PWI peers (Jones, 2016). This pattern is also consistent across states that use performance-based models.

Cyclical Underfunding and Underperformance

Because of long-term disinvestment, financial instability remains one of the most frequent challenges HBCUs face in serving their communities. Research shows that misappropriation and lack of funds are two of the main reasons why HBCUs’ accreditation is often challenged (Burnett, 2020). As HBCUs receive less money from state funding and generally have smaller endowments than their PWI counterparts (Gasman & Hilton, 2012), the money that they receive is vital to their continued survival.

The ways that HBCUs are affected by PBF vary as different models for funding are implemented in different states (Hillman & Corral, 2017). Some states do take into consideration their institutions’ mission in regard to funding models (Jones, 2016). Namely, some states have incorporated equity in the access and completion of low-income students into their PBF model. This has benefitted HBCUs and other universities with a mission of access. It further encourages institutions to remain open to enrolling students from historically marginalized backgrounds without suffering the penalties of funding formulas that uphold traditional metrics of success.

In 2013, the former Tennessee governor, Bill Haslem, implemented the Drive to 55 initiative, which aimed to ensure that 55% of Tennesseans would have a postsecondary degree or certificate by 2025 (Tennessee Higher Education Commission, n.d.). The PBF results between 2013 and 2017 did not support this initiative. Although TSU was one of only two public universities in Tennessee to increase their enrollment between 2011 and 2017, TSU remained at the bottom of appropriations received from the state during this same period (Hillman & Corral, 2017).

This is counterintuitive to the state’s stated mission for several reasons. First, TSU is growing their enrollment, which is aligned with the charge that legislators have set forth for Tennessee. Not receiving an appropriate number of appropriations places additional financial constraints on the university. Although the university has continued to increase its student enrollment, it has largely operated under the same budget from year to year. This diminishes the institution’s ability to adequately provide the student support services and academic offerings that it needs. Despite the lack of funding, the university has been able to build programs and infrastructure and increase research activity; however, it creates a cyclical problem.

In the case of TSU specifically, the effect of continued disinvestment is currently hampering the university. TSU has experienced an increase in enrollment that calls into question their fiscal practices. Their practices were examined due to the sudden need for off-campus housing because the university did not have the capacity to house all of the students. Due to complaints regarding housing and scholarship questions, The Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury performed an audit of TSU.

In this audit, it was found that TSU did not have the capacity to house the number of students who were now enrolling in the university (Mumpower, 2023). Due to the audit, it was also found that TSU did not have proper documentation practices in place in some instances. As the comptroller’s report calls into question some management practices among administration and the Board of Trustees, it also calls attention to the cyclical nature of funding. Had TSU been funded in a more equitable way, the institution may have been better prepared for the growth that it experienced.

In an attempt to conform to some of the PBF requirements, Zerquera and Ziskin (2020) asserted that institutions may begin to change their practices in ways that do not support their missions. This may result in universities changing their admission policies to ensure that they are attracting students that will help them meet the metrics set forth by the state (Zerquera & Ziskin, 2020). If institutions continue to feel pressure to conform to this standard, including HBCUs that embrace open admissions policies, it is likely that they will begin to see an enrollment decrease while also serving their communities less effectively. This would only amplify the current problems that these institutions already face in operating and securing funding.

Some states without performance-based models find themselves creative in dealing with other reasons for the shortcomings they experience in their funding sources. An example of this is the operation of colleges and universities in the State of Georgia. The HBCUs in Georgia are typically more expensive than their PWI counterparts, yet they still serve a larger portion of Black students and Pell Grant recipients (Broady et al., 2017). Working with these types of students results in a lower number of students graduating within six years, which is a major benchmark for many PBF measures.

Discussion and Implications

Although scholarship on the impact of funding policies on public HBCUs has modestly grown (e.g., Boland, 2020; Elliot, 2019; Jones, 2016; Montgomery & Montgomery, 2012), there is a greater need to understand how public policy efforts shape institutional and student outcomes for this sector. This study sought to understand the impact of PBF policies on public four-year and above HBCUs, with an emphasis on (un)intended consequences on institutional and student outcomes.

Our review of the literature largely indicated that HBCUs continue to feel the burden of long-term disinvestment and lack of policy planning that is attentive to their needs, histories, and circumstances (Boland, 2020; Saunders & Nagle, 2018). This serves as a reminder about why policy actors (e.g., state legislators) must rely on research-informed policy solutions to better advocate for institutions serving historically underserved student populations (Gándara, 2020).

The impacts of PBF policy on student performance remain highly contested across states. We found studies that have documented that PBF funding does not always increase student performance and in some instances decreases Black student enrollment despite receiving institutional premiums (Gándara & Rutherford, 2020; Rutherford & Rabovsky, 2014). Moreover, as highlighted in our findings, our examination of the literature led us to conclude that even though researchers are still evaluating the impact of PBF policies on student outcomes based on PBF 2.0, the literature affirms that PBF 1.0 has negatively impacted student performance (e.g., Ortagus et al., 2022; Rutherford & Rabovsky, 2014; Sanford & Hunter, 2011), raising several concerns about the future of state appropriations, funding formulas, and HBCUs. Despite these concerns and considering that HBCUs educate a significant share of Black students at PBF-participating states, there is a minimal share of pieces that discussed the effects of PBF policy (or public funding, to be more inclusive) explicitly at HBCUs (e.g., Boland, 2020; Elliott, 2019; Griffin, 2013; Sav, 2010). Thus, we relied on other pieces of literature that discussed PBF policy more broadly on historically marginalized or underserved students (e.g., Li, 2017, 2019; Rutherford & Rabovsky, 2014) as well as underserved institutions (Gándara & Rutherford, 2018; Sanford & Hunter, 2011).

Knowing that HBCUs have been overlooked by research on state funding, PBF, and funding formulas after conducting a systematic review of the literature, we urge state-level policy actors and legislators to avoid one-size-fits-all funding models to discuss formulas that have the potential to yield unintended consequences for HBCUs (Ortagus et al., 2020). Like Gándara and Rutherford’s (2018) recommendation, we suggest taking advantage of available tools and policy mechanisms tailored to the various types of institutions within their state, especially since many of these institutions serve diverse populations with diverse student needs. We also urge policymakers and policy advocacy centers to underscore the importance of considering institutional missions—especially those missions rooted in access—in the development of formulas for high-stakes accountability policies. Furthermore, because many of these tools and mechanisms have been historically dismissive of HBCUs (Palmer et al., 2011), we recommend consulting with research and policy organizations and public affairs teams that advocate on behalf of HBCUs and Black education, including but not limited to the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, the National Association for Equal Opportunity in Higher Education, and Howard University’s Center for HBCU for Research, Leadership, and Policy, among many others.

Administrations have approached the topic of addressing funding inequities for HBCUs differently, and how various administrations advance the interest of HBCUs is always evolving. Administrations have had different initiatives that relate to HBCUs, such as the current White House Initiative on Advancing Educational Equity, Excellence, and Economic Opportunity through Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Under the policy focus area of this current White House initiative, legislative priorities, private partnerships, and advocacy are highlighted as central features of this initiative. Research shows that these initiatives have the tendency to fall under the traps of interest convergence (Bell, 1992) and mostly benefit the interest of middle- and upper-class White communities (Cole, 2020; Gasman & Hilton, 2012). Moreover, as underscored by Elliott (2019) and Alfred (2016), neoliberal approaches to public policy undermine communication between state legislators and their constituents, especially their most vulnerable ones, which inevitably hurts public HBCUs that do not have external/legislative affairs personnel as other larger PWI flagships to effectively advocate on their behalf. Therefore, it is imperative for these initiatives—especially those coming from the executive branch of government—to be intentional about including HBCU voices, including but not limited to HBCU leaders, alumni, administrators, and policy organizations. HBCUs have unique histories and challenges; thus, it is important to stay attuned to their current realities when drafting new policy, which often involves including individuals who are directly involved with HBCUs (Sav, 2010).

To advance policy that is tailored to HBCUs, we recommend that state-level policy actors avoid making significant policy decisions that discuss MSIs as an aggregate group. Because research is still nascent about the effects of PBF policy (especially research regarding PBF 2.0) on HBCUs, it is imperative for legislators to avoid perpetuating racial equity gaps in funding by having generic and loosely targeted conversations about advancing HBCUs. Research shows that state legislators can sometimes use their intuition or “gut” instead of evidence or research to support their decision making (Gándara, 2020). As previously highlighted, state legislators, coordinating boards, and higher education systems have largely ignored the requests of their HBCUs (Palmer et al., 2011). For anyone who is seeking racial justice and more equitable funding across their institutions, it is critical to consider the unique infrastructural issues, student demographics, and personnel challenges that HBCUs face, which are different than many of their MSI and PWI counterparts given their problematic history and relationships with state leaders (Cole, 2020). We urge policy actors and educational leaders to leverage HBCU-specific research as much as possible and to rely on HBCU advocacy organizations to make informed decisions that could have the ability to affect these institutions in the long term.

Last, we found that PBF models and policies have been studied by a range of robust methodologies to understand their effects on student outcomes and policy decision making (Favero & Rutherford, 2019; McLendon et al., 2006). However, we also found that HBCUs have not been given the same methodological attention as their non-HBCU counterparts. For example, many of the studies we analyzed more broadly on PBF policy used quantitative methodologies including but not limited to DID, panel regression analyses, survival analysis, history analysis, and policy diffusion, as well as various rigorous qualitative approaches (e.g., qualitative case studies) to obtain an in-depth understanding of public policy. However, HBCU-specific studies have not received the same depth of methodological attention, and some of the studies published uniquely on HBCUs and PBF are doctoral dissertations (e.g., Alfred, 2016; Elliott, 2019; Griffin, 2013). This is not to say that doctoral dissertations are not methodologically robust; instead, we believe that it is critical to further support this scholarship by making sure it is disseminated to wider academic audiences (e.g., peer-reviewed journals) and beyond academia (e.g., policy briefs) to maximize its impact. Thus, it is imperative for government-sponsored entities, public and private philanthropies, and other nonprofit organizations interested in advancing racial equity to prioritize research funding for HBCUs and/or HBCU-related research. In addition, there are several research HBCUs that have committed to elevating their Carnegie research designation to the R1 classification (Mangan, 2022) but could benefit from additional research infrastructure (i.e., labs, grant offices, technology, research personnel) because of having to catch up with decades’ worth of state and federal disinvestments. We also know that support for PBF policies among college presidents is not consistent across the board (Rabovsky, 2014), and that public institutions have different approaches to serving their students, especially when looking at institutional types (e.g., PWIs, HBCUs). We recommend more equitable research and grant opportunities to fund HBCUs separately from other MSIs, especially since many MSIs were not so long ago PWIs and often have more robust research infrastructures. Lastly, given that states use different definitions for institutional performance outcomes as well as student outcomes, we recommend for future research to cross-examine how these definitions vary from one another (and across states) and spend time operationally defining these terms in the literature in order to inform other high-stakes accountability policies.

Conclusion

As PBF policies continue to be expanded across states (Hillman et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2022), it is essential to bring public HBCUs to the forefront of the public policy arena to ensure that these institutions are not overlooked by state-level policy planning and legislative decision making. This study sheds light on the ways in which HBCUs have been studied under the scope of public policy, especially PBF policy. Our findings reiterated the need to support more HBCU-specific scholarship to aid policy conversations. It is our hope that this study will be used to shape future research agendas as well as legislative conversations about how to best advocate for HBCUs across the nation.

Appendix

|

Author(s) |

Purpose of the Study |

Institutional Performance |

Student Outcomes |

(Un)intended Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alfred (2016) |

Exploratory multi-site case study that examines: (a) the alignment of HBCU mission statements with mandated metrics of institutional effectiveness; (b) the perceived institutional effectiveness of HBCUs by key internal and external stakeholders; and (c) the interplay of fiscal issues and institutional effectiveness in relation to the historic mission, strategic efforts, and state mandates within the context of HBCUs. |

X |

X |

X |

|

Boland (2020) |

Study that uses a differences-in-differences quasi-experimental technique to assess the impact of PBF on public four-year HBCUs. It also includes separate analyses on the older and newer models of performance funding throughout the United States. |

X |

X |

|

|

Elliott (2019) |

Case study that explores how PBF influences power relationships inside a public four-year HBCU, understands how PBF influences power relationships between an HBCU and its state, and examines how theory explains the changes taking place within an HBCU and between an HBCU and its state. |

X |

X |

|

|

Griffin (2013) |

Study explores the extent to which internal leadership stakeholders perceive the impact that PBF has had on a public HBCUs ability to maintain their university mission and to determine to what extent HBCU leaders have modified their institutional policies in order to operate under the new funding model. |

X |

X |

|

|

Jones (2016) |

Analysis of a state performance funding policy at a public HBCU. |

X |

X |

|

|

Montgomery & Montgomery (2012) |

Compares graduation rates of HBCUs to PWIs and analyzes the use of graduation rates as a performance measure for determining funding policies. |

X |

X |

Table 2. Scholarship Included in Systematic Review on the Impact of Performance-Based Funding on Historically Black Colleges and Universities

References |

|

Alfred, A. S. J. (2016). The impact of shifting funding levels on the institutional effectiveness of historically Black colleges and universities (Order No. 10172667) [Doctoral dissertation, Florida Atlanta University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Boland, W. C. (2020). Performance funding and historically Black colleges and universities: An assessment of financial incentives and baccalaureate degree production. Educational Policy, 34(4), 644–673. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904818802118 Broady, K. E., Todd, C. L., & Booth-Bell, D. (2017). Dreaming and doing at Georgia HBCUs: continued relevancy in “postracial” America. The Review of Black Political Economy, 44(1–2), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12114-017-9243-3 Coupet, J. (2017). Strings attached? Linking historically Black colleges and universities public revenue sources with efficiency. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1254427 Dougherty, K. J., Jones, S. M., Lahr, H., Natow, R. S., Pheatt, L., & Reddy, V. (2016). Performance funding for higher education: Forms, origins, impacts, and futures. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 655(1), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214541042 Elliott, K. C. (2019). The influence of state performance-based funding on public historically Black colleges and universities: A case study of race and power (Order No. 22587389) [Doctoral dissertation, Florida Atlantic University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Ellis, R. A. (2015). Performance-based funding: Equity analysis of funding distribution among state universities. Journal of Educational Issues, 1(2), 1–19. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1131597.pdf Favero, N., & Rutherford, A. (2019). Will the tide lift all boats? Examining the equity effects of performance funding policies in U.S. higher education. Research in Higher Education, 61(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09551-1 Gándara, D., & Rutherford, A. (2018). Mitigating unintended impacts? The effects of premiums for underserved populations in performance-funding policies for higher education. Research in Higher Education, 59(6), 681–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9483-x Gándara, D., & Rutherford, A. (2020). Completion at the expense of access? The relationship between performance-funding policies and access to public 4-year universities. Educational Researcher, 49(5), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20927386 Griffin, C. L. (2013). The impact of performance-based funding on the mission of a small historically Black university (Order No. 3573425) [Doctoral dissertation]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Hagood, L. P. (2019). The financial benefits and burdens of performance funding in higher education. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 41(2), 189–213. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373719837318 Hillman, N., & Corral, D. (2017). The equity implications of paying for performance in higher education. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(14), 1757–1772. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217744834 Jones, T. (2016). A historical mission in the accountability era: A public HBCU and state performance funding. Educational Policy, 30(7), 999–1041. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904815586852 Kelchen, R., & Stedrak, L. J. (2016). Does performance-based funding affect colleges’ financial priorities? Journal of Education Finance, 41(3), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1353/jef.2016.0006 Layzell., D. T. (1999). Linking performance to funding outcomes at the state level for public institutions of higher education: Past, present, and future. Research in Higher Education, 40(2), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018790815103 Letizia, A. J. (2016). Dissection of a truth regime: The narrowing effects on the public good of neoliberal discourse in the Virginia performance-based funding policy. Discourse, 37(2), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1015966 Li, A. (2017). Covet thy neighbor or “reverse policy diffusion”? State adoption of performance funding 2.0. Research in Higher Education, 58(7), 746–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-016-9444-9 Li, A. (2019). The weight of the metric: Performance funding and the retention of historically underserved students. The Journal of Higher Education, 90(6), 965–991. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2019.1602391 Lingo, M., Kelchen, R., Baker, D., Rosinger, K., Ortagus, J., & Wu, J. (2021). The landscape of state funding formulas for public colleges and universities. InformEd States. McLendon, M. K., Hearn, J. C., & Deaton, R. (2006). Called to account: Analyzing the origins and spread of state performance-accountability policies for higher education. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 28(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737028001001 Mizrahi, S. (2021). Performance funding and management in higher education: The autonomy paradox and failures in accountability. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(2), 294–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2020.1806087 Montgomery, R., & Montgomery, B. L. (2012). Graduation rates at historically Black colleges and universities: An underperforming performance measure for determining institutional funding policies. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 60(2), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2012.690623 Ortagus, J. C., Kelchen, R., Rosinger, K., & Voorhees, N. (2020). Performance-based funding in American higher education: A systematic synthesis of the intended and unintended consequences. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(4), 520–550. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373720953128 Ortagus, J., Rosinger, K., Kelchen, R., Chu, G. & Lingo, M., (2022). The unequal impacts of performance-based funding on institutional resources in higher education. InformEd States. Rutherford, A., & Rabovsky, T. (2014). Evaluating impacts of performance funding policies on student outcomes in higher education. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 655(1), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214541048 Sanford, T., & Hunter, J. M. (2011). Impact of performance funding on retention and graduation rates. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 19, 33. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v19n33.2011 Sav, G. T. (2010). Funding historically Black colleges and universities: Progress toward equality? Journal of Education Finance, 35(3), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1353/jef.0.0017 Umbricht, M. R., Fernandez, F., & Ortagus, J. C. (2017). An examination of the (un)intended consequences of performance funding in higher education. Educational Policy, 31(5), 643–673. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904815614398 Zerquera, D., & Ziskin, M. (2020). Implications of performance-based funding on equity-based missions in US higher education. Higher Education, 80(6), 1153–1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00535-0 |

References

Albritton, T. J. (2012). Educating our own: The historical legacy of HBCUs and their relevance for educating a new generation of leaders. The Urban Review, 44, 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-012-0202-9

Alfred, A. S. J. (2016). The impact of shifting funding levels on the institutional effectiveness of historically Black colleges and universities [Doctoral dissertation, Florida Atlantic University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Bell, D. A. (1992). Faces at the bottom of the well: The permanence of racism. Basic Books.

Boland, W. C. (2020). Performance funding and historically Black colleges and universities: An assessment of financial incentives and baccalaureate degree production. Educational Policy, 34(4), 644–673. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904818802118

Boland, W., & Gasman, M. (2014). America’s public HBCUs: A four state comparison of institutional capacity and state funding priorities. Penn Scholarly Commons. https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/35102

Broady, K. E., Todd, C. L., & Booth-Bell, D. (2017). Dreaming and doing at Georgia HBCUs: continued relevancy in “postracial” America. The Review of Black Political Economy, 44(1–2), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12114-017-9243-3

Burmicky, J., & McClure, K. R. (2021). Presidential leadership at broad access institutions: Analyzing literature for current applications and future research. In G. Crisp, C. Orphan, & K. R. McClure (Eds.), Unlocking opportunity through broadly accessible institutions. (pp. 163–178). Routledge.

Burmicky, J., Rzucidlo, K., Muñoz, N., Servance, W., & Thornton, M. (2022). Mattering and belonging: An HBCU case study exploration of campus involvement during the pandemic. Journal of Negro Education, 91(3), 309–321. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/901989

Burnett, C. A. (2020). Diversity under review: HBCUs and regional accreditation actions. Innovative Higher Education, 45(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-09482-w

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

Cole, E. R. (2020). The campus color line: College presidents and the struggle for Black freedom. Princeton University Press.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research. Sage.

Deming, D. J., & Figlio, D. (2016). Accountability in US education: Applying lessons from K-12 experience to higher education. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), 33–55. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.3.33

Dougherty, K. J., Jones, S. M., Lahr, H., Natow, R. S., Pheatt, L., & Reddy, V. (2016). Performance funding for higher education: Forms, origins, impacts, and futures. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 655(1), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214541042

Douglas-Gabriel, D., & Wiggins, O. (2021, March 24). Hogan signs off on $577 million for Maryland’s historically Black colleges and universities. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2021/03/24/maryland-hbcus-lawsuit-settlement/

Duran, A. (2019). Queer and of color: A systematic literature review on queer students of color in higher education scholarship. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12(4), 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000084

Elliott, K. C. (2019). The influence of state performance-based funding on public historically Black colleges and universities: A case study of race and power (Order No. 22587389) [Doctoral dissertation, Florida Atlantic University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Favero, N., & Rutherford, A. (2019). Will the tide lift all boats? Examining the equity effects of performance funding policies in U.S. higher education. Research in Higher Education, 61(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09551-1

Gándara, D. (2020). How the sausage is made: An examination of a state funding model design process. The Journal of Higher Education, 91(2), 192–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2019.1618782

Gándara, D., & Rutherford, A. (2018). Mitigating unintended impacts? The effects of premiums for underserved populations in performance-funding policies for higher education. Research in Higher Education, 59(6), 681–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9483-x

Gándara, D., & Rutherford, A. (2020). Completion at the expense of access? The relationship between performance-funding policies and access to public 4-year universities. Educational Researcher, 49(5), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20927386

Gasman, M. (2010). Comprehensive funding approaches for Historically Black Colleges and Universities. University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education and North Carolina Central University. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/331

Gasman, M., & Hilton, A. (2012). Mixed motivations, mixed results: A history of law, legislation, historically Black colleges and universities, and interest convergence. Teachers College Record, 114(7), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811211400705

Gasman, M., Nguyen, T.-H., Samayoa, A. C., & Corral, D. (2017). Minority serving institutions: A data-driven student landscape in the outcomes-based funding universe. Berkeley Review of Education, 7(1), 5–24. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1169644.pdf

Glaser, J., Spencer, K., & Charbonneau, A. (2014). Racial bias and public policy. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(1), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732214550403

Goldman, K. D., & Schmalz, K. J. (2004). The matrix method of literature reviews. Health Promotion Practice, 5(1), 5–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839903258885

Griffin, C. L. (2013). The impact of performance-based funding on the mission of a small historically Black university (Order No. 3573425) [Doctoral dissertation]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Hagood, L. P. (2019). The financial benefits and burdens of performance funding in higher education. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 41(2), 189–213. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373719837318

Harris, A. (2021). The state must provide: Why America’s colleges have always been unequal—and how to set them right. HarperCollins Publishers.

Hillman, N. W., Tandberg, D. A., & Fryar, A. H. (2015). Evaluating the impacts of “new” performance funding in higher education. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(4), 501–519. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373714560224

Hillman, N., & Corral, D. (2017). The equity implications of paying for performance in higher education. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(14), 1757–1772. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217744834

Howard University Library [HUL] (n.d.). The Washington Research Library Consortium. Retrieved from https://founders.howard.edu/about/washington-research-library-consortium-wrlc

Hu, X., Ortagus, J. C., Voorhees, N., Rosinger, K., & Kelchen, R. (2022). Disparate impacts of performance funding research incentives on research expenditures and state appropriations. AERA Open, 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211071109

Jones, T. (2016). A historical mission in the accountability era: A public HBCU and state performance funding. Educational Policy, 30(7), 999–1041. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904815586852

Kelchen, R., Ortagus, J., Rosinger, K., & Cassell, A. (2023). Investing in the workforce: The impact of performance-based funding on student earnings outcomes. The Journal of Higher Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2023.2171201

Kelchen, R. (2018). Higher education accountability (1st ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Li, A. (2017). Covet thy neighbor or “reverse policy diffusion”? State adoption of performance funding 2.0. Research in Higher Education, 58(7), 746–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-016-9444-9

Li, A. (2019). The weight of the metric: Performance funding and the retention of historically underserved students. The Journal of Higher Education, 90(6), 965–991. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2019.1602391

Lingo, M., Kelchen, R., Baker, D., Rosinger, K., Ortagus, J., & Wu, J. (2021). The landscape of state funding formulas for public colleges and universities. InformEd States.

Mangan, K. (2022). A race to the top in research. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved February 2022, from https://www.chronicle.com/article/a-race-to-the-top-in-research?utm_source=Iterable&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=campaign_3592470_nl_Academe-Today_date_20220126&cid=at&source=ams&sourceid=&cid2=gen_login_refresh&cid2=gen_login_refresh

McDonnell, L. M., & Elmore, R. F. (1987). Getting the job done: Alternative policy instruments. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 9(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163726

McLendon, M. K., Hearn, J. C., & Deaton, R. (2006). Called to account: Analyzing the origins and spread of state performance-accountability policies for higher education. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 28(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737028001001

Miller, G. N., Lynn, F. B., & McCloud, L. I. (2021). By lack of reciprocity: Positioning historically Black colleges and universities in the organizational field of higher education, The Journal of Higher Education, 92(2), 194–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2020.1803026

Montgomery, R., & Montgomery, B. L. (2012). Graduation rates at historically Black colleges and universities: An underperforming performance measure for determining institutional funding policies. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 60(2), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2012.690623

Mumpower, J. (2023). Controller’s special report Tennessee State University.

Neuman, M., & Gough, D. (2020). Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. In O. Zawacki-Richter, M. Kerres, S. Bedenlier, M. Bond, & K. Buntins (Eds.), Systematic reviews in educational research (pp. 3–22). Springer.

Orphan, C. M. (2020). Not all regional public universities strive for prestige: Examining and strengthening mission-centeredness within a vital sector. New Directions for Higher Education, 2020(190), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20364

Ortagus, J. C., Rosinger, K. O., Kelchen, R., Chu, G., & Lingo, M. (2023). The unequal impacts of performance-based funding on institutional resources in higher education. Research in Higher Education, 64(5), 705–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-022-09719-2

Ortagus, J., Rosinger, K., Kelchen, R., Chu, G., & Lingo, M. (2022). The unequal impacts of performance-based funding on institutional resources in higher education. InformEd States.

Ortagus, J. C., Kelchen, R., Rosinger, K., & Voorhees, N. (2020). Performance-based funding in American higher education: A systematic synthesis of the intended and unintended consequences. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(4), 520–550. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373720953128

Palmer, R. T., Davis, R. J., & Gasman, M. (2011). A matter of diversity, equity, and necessity: The tension between Maryland’s higher education system and its historically Black colleges and universities over the office of civil rights agreement. The Journal of Negro Education, 80(2), 121–133.

Ra, E., Kim, J., Hong, J., & DesJardins, S. L. (2023). Functioning or dysfunctioning? The effects of performance-based funding. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 45(1), 79–107. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737221094563

Rabovsky, T. (2014). Support for performance-based funding: The role of political ideology, performance, and dysfunctional information environments. Public Administration Review, 74(6), 761–774. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24029501

Rosinger, K., Ortagus, J., Kelchen, R., Cassell, A., & Voorhees, N. (2020). The landscape of performance-based funding in 2020. InformEd States.

Rosli, A., & Rossi, F. (2016). Third-mission policy goals and incentives from performance-based funding: Are they aligned? Research Evaluation, 25(4), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvw012

Rutherford, A., & Rabovsky, T. (2014). Evaluating impacts of performance funding policies on student outcomes in higher education. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 655(1), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214541048

Sanford, T., & Hunter, J. M. (2011). Impact of performance funding on retention and graduation rates. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 19, 33. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v19n33.2011

Saunders, K. M., & Nagle, B. T. (2018). HBCUs punching above their weight: A state-level analysis of historically Black college and university enrollment graduation. UNCF Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute.

Sav, G. T. (2010). Funding historically Black colleges and universities: Progress toward equality? Journal of Education Finance, 35(3), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1353/jef.0.0017

Strayhorn, T. L. (2020). Measuring the influence of internship participation on Black business majors’ academic performance at historically Black colleges and universities. Journal of African American Studies, 24(2020), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-020-09501-7

Tennessee Higher Education Commission. (n.d.). HBCU success. Retrieved from https://www.tn.gov/thec/hbcu-success.html#:~:text=Tennessee%20is%20home%20to%20seven,of%20the%20state’s%20Grand%20Divisions.