What Does “Success” Mean to Students at a Selective University? Individual Differences and Implications for Well-Being

Malorie Lipstein1, Michelle Wong2, & Bridgette Martin Hard1*

1Duke University

2Harvard University

Abstract

This study investigated how college students (N = 376) at a private, selective university (a) define success in college in their own words, and how conceptions of success (b) relate to differences in motivation and other individual differences, and (c) predict well-being. A thematic analysis suggested that students’ definitions of success were multifaceted, but the most common themes reflected academic and social criteria for success. Students who defined success in terms of Experience (e.g., trying new things) and Future-Readiness (e.g., preparedness to handle life after college) tended to be higher in mastery orientation and intrinsic motivation. Success definitions varied with demographic characteristics, including gender, class year, race, first-generation status, academic interests, and more, in ways that likely reflect differences in students’ cultural backgrounds and interests. Finally, well-being was higher in students who defined success in terms of Intellectual Growth (e.g., learning, being challenged, determining academic interests). We discuss the implications of these findings for practice (e.g., for university administrators, faculty, and advisors) and for future research.

Keywords: student attitudes, undergraduate students, student characteristics, student well-being, academic motivation, demographic differences, success

* Contact: bridgette.hard@duke.edu

© 2023 Lipstein et al. This open access article is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

What Does “Success” Mean to Students at a Selective University? Individual Differences and Implications for Well-Being

What does success in college mean? Stereotypes of a successful college student may call to mind top grades, impressive awards, leadership roles, and membership in prestigious organizations. Yet, success likely takes on unique meanings for different students. Prior research suggests that college students define success as a combination and balance of numerous criteria (e.g., Yazedjian et al., 2008), that measures of success like academic achievement are linked to student characteristics (e.g., Travers et al., 2014), and that internal criteria for success are related to higher well-being (e.g., Gill et al., 2021). The present study leveraged a mixed-methods approach to develop a clearer picture of how students define success. We focused specifically on students attending a private, selective university who experience a unique set of pressures to succeed in a high-achieving environment. We also aimed to understand how students’ definitions vary, and how they relate to the greater college experience. A long-term goal of this work was to generate insights that could guide administrators and instructors in developing better approaches to support student achievement and well-being. We used open-ended questions and three inventories to address the following research questions:

- 1. How do undergraduate students at a private, selective university define success in college, in their own words?

- 2. How do students’ conceptualizations of success relate to individual differences in academic motivation, goal orientation, and demographic characteristics?

- 3. Do students’ conceptualizations of success relate to their subjective well-being?

In the following sections, we review the literature on college success and related constructs that informed our goals and predictions.

Literature Review

Defining Success in the University Setting

The first major goal of our research was to understand how university students define success, in their own words, using a qualitative approach of analyzing the most common themes in their responses. Previous work based on focus group interviews at large public universities suggests that college students define success based on a balance of academic achievement, social integration, and ability to independently navigate college life (Yazedjian et al., 2008). The idea that college students conceptualize success in terms of balance is sensible given that balancing time across different domains (e.g., physical, intellectual, emotional, social, etc.) predicts aspects of actual success, such as academic achievement (e.g., Horton & Snyder, 2009). We thus might expect students’ definitions of success to reflect balance, particularly given the context of a highly selective university. Students at highly selective undergraduate programs report experiencing pressure to be especially “well-balanced,” meaning to juggle academics, friends, jobs, commitment to organizations, and leadership roles (Kerrigan et al., 2017). Therefore, we examined whether our participants’ success definitions reflected notions of well-roundedness and balance through the inclusion of multiple domains (e.g., academics and social life) or specific mentions of “balance” in defining success.

Previous work also suggests that students tend to focus more on academic achievement (i.e., good grades) than engagement (i.e., wanting to learn and explore academically) in defining success. One study explored how undergraduates at liberal arts colleges in New England conceptualized a successful year in college using a qualitative approach (Jennings et al., 2013). Students in this sample were more likely to define college success in terms of their own and others’ academic achievements like grades rather than academic engagement, which included desire to learn and gain knowledge in interesting classes. With these prior findings in mind, we thus examined whether themes related to academic achievement were more common in defining success than themes related to academic engagement.

Linking Conceptualizations of Success to Student Characteristics

Our second major goal was to evaluate how conceptualizations of success, in terms of common themes, vary with student characteristics, specifically academic motivation, goal orientation, and demographic characteristics. Although prior work has linked these individual differences to achievement, as described in the sections that follow, the relationship between these individual differences and how students define success has yet to be explored.

One characteristic that might be linked to conceptualizations of success is academic motivation. In their review of the literature on academic motivation, Ryan and Deci (2020) explain that academic motivation operates on a continuum from extrinsic motivation (the desire to reap a tangible benefit or avoid unpleasant results) to intrinsic motivation (the innate satisfaction of an action or behavior) with many levels in between that contain elements of both. Importantly, more intrinsic levels of motivation predict students’ higher grades, engagement, learning, and wellness. However, prior work has not addressed whether academic motivation connects to how undergraduates think about success. We expected that college students’ definitions of success would reflect different styles of academic motivation. Intrinsically motivated students might consider success as learning from their schoolwork or forging meaningful relationships, whereas extrinsically motivated students might define success based on tangible achievements such as academic honors and post-graduation salaries.

Another construct closely related to student motivation and success is achievement goal theory, which centers around learners’ mastery and performance goals. Mastery goals reflect an individual’s desire to grow, personally develop, and gain knowledge or skills, whereas performance goals reflect the desire to outperform others. Mastery-oriented students also tend to be higher in intrinsic motivation, whereas performance-oriented students tend to be more extrinsically motivated (Urdan & Kaplan, 2020). Orientation towards mastery goals, especially those that relate to personal growth, is associated with various positive academic outcomes, such as knowledge acquisition and self-monitoring of thought processes (Jo et al., 2021), greater enjoyment of academic work and ability to change misconceptions (Stewart et al., 2016), and academic performance (Travers et al., 2014). Performance goal orientation is also linked to positive academic outcomes like higher exam grades and vigilant study strategies (Senko, 2019).

Given prior evidence that goal orientation predicts success-related outcomes, goal orientation might also relate to different ways that students define success. We expected that students oriented towards mastery goals would be more likely to conceptualize success as gaining meaningful knowledge and skills, whereas students oriented towards performance goals would more likely define success in terms of traditional achievement measures like grade point average (GPA) or acceptance to prestigious post-graduation programs.

We also explored differences in definitions of success across a variety of demographic characteristics, including gender, class year, academic program (arts and sciences vs. engineering), and status as a student-athlete or pre-medical student. In addition, we investigated potential differences as a function of belonging to traditionally marginalized groups that can experience barriers to success in college. Past research has found that racial minority students experience pressure to perform academically, negative stereotypes, racial/ethnic discrimination, and financial pressure (Henry, 2006). International undergraduates, who struggle with English language and culture, have also been found to experience poor social and academic adjustment (Andrade, 2006). Many first-generation students struggle socially and academically in their transition to college campuses as well, with limited understanding of cultural norms and familial support (Pascarella et al., 2004). Such barriers to college life and achievement could impact the ways traditionally less privileged students conceptualize success.

Linking Conceptualizations of Success and Well-Being

The third goal of the present research was to examine how definitions of success are related to well-being. Internal criteria for success like striving for personal growth tend to be linked to higher well-being more than extrinsic criteria like GPA (Gill et al., 2021). However, prior work suggests that students may define success in ways that over-value extrinsic criteria. In one study, for example, students rated external indicators related to grades or completing courses as the most important measures of success whether using Likert type surveys or quadratic voting methods (Naylor, 2017). Given these prior findings, we expected that students who define success more in terms of internal, rather than external, criteria might experience higher levels of well-being.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 394 undergraduate students at a private, selective National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) university in the Southeast United States, with an acceptance rate of less than 10%. We recruited two subsamples, with the goal of representing a wide variety of students at the institution. One subsample (n = 273) was recruited via emails from their introductory psychology course professor that offered a bonus point on their lowest exam score at the end of the semester if they completed two surveys that included measures for this study. A second subsample (n = 103) were students enrolled at the same institution, recruited via a snowball survey distributed to students through word of mouth and social media. We distributed a link to the survey using text messages, Instagram, and Facebook and encouraged students to share with others. Students who completed the survey were entered into a lottery for a $25 Amazon gift card (50 gift cards were distributed). Five students from the snowball sample had already completed the survey in their introductory psychology course; survey responses only from the psychology course were included in analyses in these cases. Eighteen other participants were excluded for non-student status, repeated answers, and self-reported age outside of the college range (17 to 22). Our final sample size was 376 participants. Table 1 summarizes demographic information for both samples.

Procedure

All participants completed a survey delivered through Qualtrics survey software. The survey, which also contained questions for another research project (see supplemental materials provided on Open Science Framework, for additional details: https://osf.io/be6fr/?view_only=c5193320649f4c2a8b2b268a4f890621), took approximately 10–15 min to complete and was approved by the University Campus Institutional Review Board. All data were collected between November and December 2021.

Measures

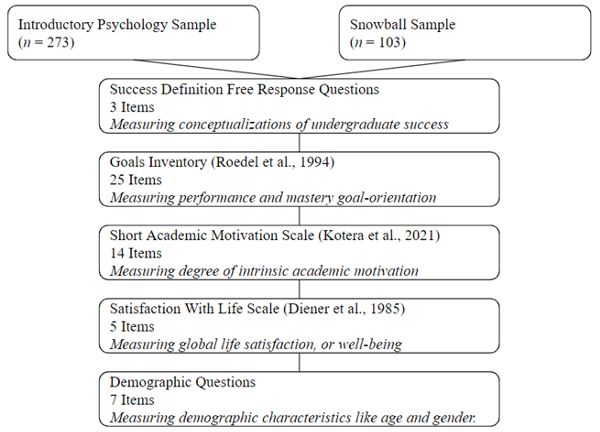

Key survey measures and their flow are represented by Figure 1. All measures are available in the supplemental material on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/be6fr/?view_only=c5193320649f4c2a8b2b268a4f890621).

Student Definitions of Success

Participants described their definitions of success in a response to the question “Define what success in college means to you.” Responses ranged from 119 to 684 characters in length. We also asked students two other questions related to their definitions of success: “How is your definition of success in college similar to other [UNIVERSITY NAME] students’ definitions?,” and “How is your definition of success in college different from other [UNIVERSITY NAME] students’ definitions?” Although these additional questions are not the focus of the present paper, we performed analyses of student responses to these questions that are available in the supplemental material on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/be6fr/?view_only=c5193320649f4c2a8b2b268a4f890621).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Samples

|

Total Sample (N = 376) |

Introductory Psychology Sample (n = 273) |

Snowball Sample (n = 103) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

|||

|

Female |

60.1% |

61.8% |

55.9% |

|

Male |

36.8% |

34.4% |

43.1% |

|

Other |

3.0% |

3.9% |

1.0% |

|

Class |

|||

|

First Year |

42.7% |

50.2% |

22.5% |

|

Sophomore |

29.9% |

33.3% |

20.6% |

|

Junior |

14.1% |

12.8% |

17.6% |

|

Senior |

13.1% |

3.3% |

39.2% |

|

Race |

|||

|

Asian |

30.8% |

30.9% |

30.7% |

|

Black or African American |

5.0% |

5.8% |

3.0% |

|

Hispanic/Latino |

3.6% |

4.2% |

2.0% |

|

Native American or Alaskan Native |

1.4% |

1.5% |

1.0% |

|

White |

44.2% |

41.7% |

50.5% |

|

Multiracial |

14.2% |

14.7% |

12.9% |

|

Other |

0.8% |

1.2% |

— |

Goal Orientation

To assess orientation towards mastery or performance goals in academic settings, participants completed eight items from the 25-item Goals Inventory (Roedel et al., 1994). Participants rated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each statement on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Four items (i.e., “I am naturally motivated to learn”) reflected mastery goals, and four items (i.e., “I feel angry when I do not do as well as others”) represented performance goals. Scores on mastery goal and performance goal items both demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability (α = .68, α = .75, respectively).

Figure 1. Procedure Overview: Samples and Survey Flow

Note. Figure 1 only includes key measures utilized in analyses for this paper. The full set of survey materials are available in the supplemental material on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/be6fr/?view_only=c5193320649f4c2a8b2b268a4f890621).

Academic Motivation

The Short Academic Motivation Scale is a 14-item measure of students’ motivation on a continuum from amotivation to intrinsic motivation, including a total of seven subscales of motivation that are increasingly intrinsic in nature (Kotera et al., 2021). Participants rated the extent to which each of the 14 statements corresponded to one of the reasons they attended college on a 5-point scale (1 = Does not correspond at all to 5 = Corresponds exactly). Two items correspond to each of the seven levels of academic motivation: amotivation (i.e., “I can’t see why I go to college and frankly, I couldn’t care less”), external regulation (i.e., “In order to obtain a more prestigious job later on”), introjected regulation (i.e., “Because I want to show myself that I can succeed in my studies”), identified regulation (i.e., “Because I think that a college education will help me better prepare for the career I have chosen”), intrinsic motivation to experience stimulation1 (i.e., “For the pleasure that I experience when I feel completely absorbed by interesting subjects”), intrinsic motivation toward accomplishment (i.e., “For the pleasure that I experience while I am surpassing myself in one of my personal accomplishments”), and intrinsic motivation to know (i.e., “For the pleasure I experience when I discover new things never seen before”). Higher scores on a given subscale reveals participants’ predominant style of academic motivation. Scores on the adapted subscale demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability (α = .67), as did scores on the other subscales (α ranged from .72 to .87).

Subjective Well-Being

Participants completed the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale, focusing on global life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985). Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each statement (i.e., “The conditions of my life are excellent.”) on a 7-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree). Higher scores correspond to higher well-being (α = .83).

Results

Data Analysis

Students’ definitions of success were analyzed qualitatively using an iterative thematic coding technique proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). The first author read the entire corpus of responses, looking for patterns in the data and generating a rough list of themes and sub-themes that stood out in students’ conceptualizations of success. As this process was repeated for a second time, the preliminary list of themes was modified to combine repetitive ideas, break down main themes into more sub-themes, and finalize names and definitions for each theme. Next, each response was coded to note which themes and subthemes were present. The second author coded a subset of the responses (10%) to determine interrater reliability, which was strong, with a Cohen’s κ of .987. The final set of themes and subthemes included in this paper were present in at least 5% of students’ responses.

Quantitative analyses were performed in Jamovi, an open-source statistical software where statistical tests and data cleaning and analysis can be completed. We conducted bivariate correlations and chi-square tests to explore the relationships between students’ success definition themes, individual differences, and well-being.

What Themes Are Present in Students’ Definitions of Success in College?

Our first research question aimed to identify how students at a private, selective university defined success. Using the thematic coding technique, we identified 13 major themes in students’ responses, described in detail in Table 2 along with examples of definitions coded for each theme. In order from most to least common, these themes were Social Life, Academic Performance, Future-Readiness, Intellectual Growth, Professional and Post-Grad Plans, Personal Growth, Enjoyment, Balance, Extracurriculars, Experience, Individualized Goals, Health, and Working Hard. For several major themes, we noted subthemes that were common (present in at least 5% of the total responses) but did vary across individuals coded for that theme. One of these subthemes, Meaningful Relationships, also had common subthemes (again, present in at least 5% of the total responses). These nested subthemes are also reported in Table 2 in order of frequency.

The most common theme, found in more than half (56.7%) of students’ definitions, was Social Life, which captured various aspects of students’ friendships and other relationships. Academic Performance was the second most common theme, present in about half (52.1%) of responses. This theme focused on academic aspects of success, such as good grades, GPA, classroom achievement, being on the dean’s list, and getting degrees. The least common themes were Working Hard (e.g., giving one’s best effort), found in 7.5% of responses and Health (e.g., mental health, physical health, general well-being), found in 9.6% of definitions.

Students’ definitions reflected balance, explicitly mentioned as a theme in 17.6% of responses and implicated by the number of themes each response included. On average, student definitions included 3.2 major themes, with a range of zero to nine. Students’ responses also emphasized themes related to academic achievement (52.1% included Academic Performance) more than themes related to academic engagement (30.9% included Intellectual Growth).

Table 2. Common Themes in Question 1 Responses: “Define what success in college means to you.”

|

Theme |

% of Overall Responses (% of subtheme within the “parent” theme) |

Description |

Example |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Social Life |

56.65% |

Responses that discuss social life, friendships, relationships with anyone on campus including students, professors, faculty, and mentors |

“Success is both getting good grades and having a strong social life. This requires balancing multiple aspects of college.” |

|

Subtheme: Meaningful Relationships |

41.49% (73.24%) |

Responses that highlight creating meaningful relationships with interesting/good/high-quality people, long-lasting bonds |

“Success for me means not only getting good grades but also making meaningful connections with others . . . [UNIVERSITY NAME] offers a lot of opportunities to meet cool people that you can’t necessarily get elsewhere.” |

|

Nested Subtheme: Friends |

23.14% (55.77%) |

Responses that mention creating meaningful or long-lasting friendships |

“Finding a strong support group of friends that I can remain in contact consistently after college is very important to me.” |

|

Nested Subtheme: Having a Network |

6.12% (14.74%) |

Responses that mention building a network |

“Success in college means creating an important network of interpersonal contacts.” |

|

Subtheme: Meeting New People |

7.18% (12.68%) |

Responses that refer to being introduced to/meeting new people |

“Success means graduating with a degree of your interest and meeting great people along the way.” |

|

Academic Performance |

52.13% |

Responses that quantify success through good grades, GPA, classroom achievement (or “doing well” in class), dean’s list, getting degrees |

“Success in college means earning straight A’s, making the dean’s list, and graduating with a fairly high GPA.” |

|

Future-Readiness |

34.31% |

Responses that define success as being prepared to handle life after college |

“Success means learning new things, making life-long friendships, and finding what I am interested in. I hope that I can leave college prepared for my next stage in life.” |

|

Subtheme: Passions and Interests |

13.30% (38.76%) |

Responses that discuss identifying and exploring passions/interests/hobbies (excluding academic interests like choosing a major) |

“Success in college means finding something (or somethings) that you are passionate about. True success is when you can turn these passions (that make you happy as a result) into something you can spend doing the rest of your life.” |

|

Subtheme: Life Direction |

12.77% (37.21%) |

Responses about having overall direction or a life path, finding your way and what you want to do (can be career-oriented or in general) |

“Success in college means finding a good community and exploring the things you love. While academic achievement is important, it is more necessary to begin to figure out what direction you truly want your life to head.” |

|

Intellectual Growth |

30.85% |

Responses that point towards success as measured by how much students have learned and are challenged, determining academic interests |

“Becoming smarter and accumulating knowledge.” |

|

Subtheme: Learning |

20.48% (66.38%) |

Responses that mention learning about new concepts or fields, gaining knowledge |

“Success in college is defined based on your understanding of the material and should not be boiled down simply to grades; how well do you understand what you’re learning, rather than how good are you at getting an ‘A’.” |

|

Subtheme: Academic Direction |

8.51% (27.59%) |

Responses that are about narrowing down academic interests to the right major/field, figuring out what you want to do/study and doing well at it |

“Success in college, in my opinion, means to find academic subjects that interest me while creating a clearer vision on what I want to do in my life as well as doing well in those classes.” |

|

Professional and Post-Grad Plans |

26.33% |

Responses that define success as acceptance to med school, law school, masters/PhD programs, or prestigious/high-paying internships and jobs |

“Leaving with a good paying job or acceptance to further pursue an education.” |

|

Subtheme: Professional Development |

7.18% (27.27%) |

Responses that consider becoming a competent/an asset, having the tools, knowledge, and skills for a career; prepared for a career |

“Being proud of the work you’ve done and setting yourself up for a job or success for the future after graduation with proper resources and connections.” |

|

Personal Growth |

25.00% |

Responses that suggest that college’s greater purpose is to help students mature, learn about themselves, become better people, step out of their comfort zones, and grow from mistakes |

“Success to me means learning (not necessarily good grades), making social connections, and maturing as a person. College for me is also a lot about stepping outside my comfort zone and experiencing new things.” |

|

Subtheme: Finding Identity |

8.78% (35.11%) |

Responses that include notions of solidifying/becoming more confident in personal values, morals, purpose, independence, and/or identity |

“Being able to be confident and comfortable with yourself is incredibly important to develop your own identity.” |

|

Enjoyment |

18.88% |

Responses that refer to being happy, content, enjoying classes or social life, having fun, or creating memories |

“First, you’ve gotta have a good time. If you aren’t having a good time, you fail.” |

|

Balance |

17.55% |

Responses that explicitly refer to success as a combination or balance of multiple criteria (i.e. academics, social life, happiness, health, extracurriculars, professional opportunities); being well-rounded |

“Success in college means performing well academically while also balancing mental health, physical health, social life, and sleep. It means doing what makes you happy, while also setting yourself up for future success in life.” |

|

Extracurriculars |

17.29% |

Responses that mention extracurricular activities (clubs, charity work, athletics, research, leadership positions, or any other student organization) |

“For me, success in college means me doing well in all my classes, engaging in campus activities, and creating a community of friends that I trust. I want to be involved in more clubs and groups on campus to help facilitate this process and make my time here more meaningful.” |

|

Experience |

15.16% |

Responses that mention trying new things, having no regrets, or having a meaningful/fulfilling college experience overall |

“Success in college to me means being able to experience every aspect of it to the fullest. I don’t believe that getting all A’s in college indicates that I was successful. I would much rather sacrifice some of my grades to experience things much more meaningful that college has to offer. Whether its intriguing extracurriculars or exploring research/projects that are meaningful to me, I would consider my college experience successful if I come out of it with no regrets.” |

|

Subtheme: Resources/ Opportunities |

5.59% (36.84%) |

Responses that mention using available resources/opportunities and taking advantage of everything college has to offer |

“Success in college for me includes academic success meaning working hard and doing well in my courses. It also means using my time and resources to the fullest extent and getting the most out of my college experience, especially in regards to exploring career interests and opportunities.” |

|

Individualized Goals |

11.17% |

Responses that consider success in college to be a subjective construct based on achieving one’s personally defined goals or standards, being proud |

“Success in college means that you are satisfied with the outcome of your hard work. I don’t think success has to be quantitative, like a score on an exam; success is being satisfied with the results of one’s efforts.” |

|

Health |

9.57% |

Responses that regard success in terms of maintaining or growing physical or mental health/wellbeing, self-care, getting enough sleep and exercise |

“a big component to success is maintaining a healthy lifestyle.” |

|

Subtheme: Emotional/ Mental |

5.59% (58.33%) |

Responses that highlight maintaining a positive mental state, handling stress |

“Firstly, success in college means taking care of my mental health.” |

|

Working Hard |

7.45% |

Responses that consider a student who has given their best effort to be successful or that success is a “return on investment” that students have made in terms of hard work, time, effort, or tuition |

“Getting my hard work come into fruition by maintaining righteousness, faith, cooperation, and getting into medical schools.” |

Note. Bolded text is included to emphasize words and phrases that specifically illustrate the relevant theme.

How Do Students’ Success Definitions Relate to Differences in Goal Orientation and Academic Motivation?

Once we determined which themes students included in their success definitions, our second research question aimed to evaluate how students’ conceptualizations of success (i.e., themes) related to student characteristics. We began by examining individual differences in goal orientation and academic motivation. We focused on themes present in at least 10% of students’ success definitions and conducted bivariate correlations to measure the relationship between the presence of each theme, goal orientation, and academic motivation. Significant bivariate correlations are described below. Descriptive statistics for goal orientation and academic motivation, along with a few demographic differences we found for these measures, are described on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/be6fr/?view_only=c5193320649f4c2a8b2b268a4f890621).

In terms of goal orientation, students higher in mastery-orientation (M = 16.0, SD = 2.4) were significantly more likely to include the theme of Experience (e.g., trying new things, having no regrets or a meaningful/fulfilling college experience) in their success definitions, r (374) = .11, p < .05. Students who scored higher on performance-orientation (M = 13.1, SD = 3.2) were significantly less likely to include the Future-Readiness theme (e.g., preparedness to handle life after college, world perspective) in their success definitions, r (374) = −.11, p < .05.

In terms of academic motivation, students who scored higher on intrinsic motivation to know (M = 7.3, SD = 1.7; e.g., being motivated by the feeling of gaining knowledge) were significantly more likely to include Experience (e.g., trying new things, having no regrets or a meaningful/fulfilling college experience) as a theme in their success definitions, r (374) = .11, p < .05. Students who scored higher on introjected regulation (M = 6.4, SD = 2.1; e.g., being motivated by a tangible, self-enforced outcome) were significantly more likely to mention Extracurriculars (e.g., clubs, charity work, athletics, research, leadership positions, other student organizations), r (374) = .11, p < .05, and Balance (e.g., well-roundedness, requiring multiple types of success), r (374) = .11, p < .05, but significantly less likely to mention Experience, r (374) = −.14, p < .05. Students who scored higher on external regulation (M = 7.6, SD = 2.0; e.g., being motivated by a tangible outcome enforced by others) were significantly less likely to include Experience, r (374) = −.14, p < .01, and Future-Readiness (e.g., preparedness to handle life after college, world perspective), r (374) = −.12, p < .05, in defining success. These patterns show how students’ degree of intrinsic or extrinsic motivation were reflected in their definitions.

How Are Students’ Success Definitions Related to Demographic Characteristics?

Next, we performed a series of chi-square tests of independence to examine the relationships between success definition themes present in 10% or more of answers and demographic characteristics. Significant differences in success definition themes by demographic characteristics are described below.

Women and other non-male-identifying students2 were more likely (29.4%) to mention the Personal Growth (e.g., maturing, learning about oneself, becoming a better person, stepping out of comfort zones) theme than male-identifying students (19.5%), χ2(1, N = 361) = 4.25, p = .039. Women and other non-male-identifying students were also more likely (37.7%) to mention Intellectual Growth (e.g., learning, being challenged, determining academic interests) than male-identifying students (19.5%), χ2(1, N = 361) = 13.0, p < .001.

The university where we conducted our research has an arts and sciences school and an engineering school. Arts and sciences students were more likely (55.2%) to mention Academic Performance than engineering students (34.7%), χ2(1, N = 375) = 7.19, p = .007. Arts and sciences students were also more likely (59.2%) to mention Social Life (e.g., social life, friendships, relationships) than engineering students (42.9%), χ2(1, N = 375) = 4.65, p = .031.

Table 3. Bivariate Correlations (Pearson’s r) Between Success Definition Themes and Goal Orientation, Academic Motivation, and Well-Being

|

Academic Performance |

Social Life |

Extracurriculars |

Professional and Post-Grad Plans |

Experience |

Personal Growth |

Intellectual Growth |

Future-Readiness |

Enjoyment |

Balance |

Individualized Goals |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mastery Goals |

0.087 |

−0.065 |

0.047 |

0.007 |

0.108* |

−0.01 |

0.066 |

0.018 |

0.015 |

−0.016 |

−0.019 |

|

Performance Goals |

0.099 |

−0.021 |

0.015 |

−0.046 |

−0.017 |

−0.042 |

0.053 |

−0.11* |

−0.004 |

0.066 |

−0.018 |

|

Intrinsic Motivation to Know |

0.022 |

−0.055 |

0.008 |

0.021 |

0.107* |

0.076 |

0.057 |

0.051 |

0.004 |

0.017 |

0.014 |

|

Intrinsic Motivation Towards Accomplishment |

0.066 |

0 |

0.056 |

−0.002 |

0.077 |

0.057 |

0.094 |

0.031 |

−0.038 |

0.034 |

0.023 |

|

Intrinsic Motivation to Experience Stimulation |

0.061 |

−0.025 |

0.07 |

−0.001 |

−0.002 |

0.062 |

−0.006 |

0.003 |

0.017 |

0.018 |

0.042 |

|

Identified Regulation |

0.005 |

−0.002 |

0.009 |

−0.009 |

−0.065 |

0.049 |

0.055 |

−0.057 |

−0.035 |

0.006 |

0.033 |

|

Introjected Regulation |

0.073 |

0.046 |

0.107* |

−0.075 |

−0.103* |

0.021 |

0.031 |

−0.033 |

−0.052 |

0.106* |

0.052 |

|

Amotivation |

0.054 |

0.063 |

0.038 |

−0.039 |

−0.049 |

−0.085 |

−0.051 |

−0.063 |

0.042 |

0.046 |

0.035 |

|

External Regulation |

0.019 |

−0.014 |

−0.009 |

0.036 |

−0.138** |

−0.018 |

−0.032 |

−0.122* |

−0.052 |

0.032 |

0.039 |

|

Satisfaction With Life |

−0.087 |

−0.039 |

−0.049 |

−0.029 |

0.073 |

0.064 |

0.102* |

0.063 |

0.001 |

−0.113* |

0.003 |

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Class year was significantly associated with Professional and Post-Grad Plans (e.g., acceptance to post-graduate programs or prestigious/high-paying internships and jobs), χ2(4, N = 375) = 13.5, p = .009. Juniors mentioned (39.6%) this theme most, followed by sophomores (31.3%), seniors (30.6%), and first-year undergraduates (17.5%).

Pre-medical students, making up 34.0% of the overall sample, were more likely (34.1%) to mention Professional and Post-Grad Plans (e.g., acceptance to medical school) than non-pre-medical students (22.2%), χ2(1, N = 259) = 4.23, p = .040. Pre-medical students were also more likely (21.6%) to mention Experience (e.g., trying new things, having no regrets or a meaningful/fulfilling college experience) in their definitions of success than non-pre-medical students (11.1%), χ2(1, N = 259) = 5.10, p = .024.

Student-athletes, who made up 14.3% of the overall sample, were more likely (70.3%) to mention the Academic Performance theme (e.g., good grades, GPA, classroom achievement, dean’s list, getting degrees) than non-athletes (50.5%), χ2(1, N = 259) = 6.47, p = .011. Athletes were also more likely (35.1%) to include Extracurriculars (e.g., clubs, charity work, athletics, research, leadership positions, other student organizations) in their definitions than non-athletes (15.3%), χ2(1, N = 259) = 8.39, p = .004.

We recoded race based on whether students identified holding a racial identity (participants could select multiple racial categories) from a traditionally marginalized racial minority (RM) group (Hispanic/Latino, Black or African American, Native American or Alaskan Native, and Other Race [n = 77]) or not (non-RM; White and Asian [n = 283]). Several themes were more common in the success definitions of non-RM students than RM students, including Social Life (61.5% vs. 45.5%; e.g., social life, friendships, relationships), χ2(1, N = 360) = 6.39, p = .011, Extracurriculars (20.1% vs. 10.4%; e.g., clubs, charity work, athletics, research, leadership positions, other student organizations), χ2(1, N = 360) = 3.89, p = .049, and Experience (17.3% vs. 7.8%; e.g., trying new things, having no regrets or a meaningful/fulfilling college experience), χ2(1, N = 360) = 4.24, p = .039.

International students, who made up 9.7% of the overall sample, were more likely (58.5%) to mention Social Life (e.g., social life, friendships, relationships) than non-international students (32.0%), χ2(1, N = 259) = 6.46, p = .011.

First-generation (FG) students, who did not have at least one parent with a 4-year college degree, made up 9.6% of the overall sample, and were more likely (22.2%) to cite Individualized Goals (e.g., achieving personally defined goals or standards, being proud) than continuing-generation students (9.7%), χ2(1, N = 361) = 5.21, p = .022.

Table 4. Significant Chi-Square Associations Between Success Definition Themes and Demographic Characteristics

|

χ2 Value |

df |

p |

N |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender x Intellectual Growth |

13 |

1 |

< .001 |

361 |

|

NCAA Student-Athlete Status x Extracurriculars |

8.39 |

1 |

0.004 |

259 |

|

School (Arts and Sciences vs. Engineering) x Academic Performance |

7.19 |

1 |

0.007 |

375 |

|

Class Year x Professional and Post-Grad Plans |

13.5 |

4 |

0.009 |

375 |

|

NCAA Student-Athlete Status x Academic Performance |

6.47 |

1 |

0.011 |

259 |

|

Race x Social Life |

6.39 |

1 |

0.011 |

360 |

|

International Student Status x Social Life |

6.46 |

1 |

0.011 |

259 |

|

First-Generation Student Status x Individualized Goals |

5.21 |

1 |

0.022 |

375 |

|

Pre-Medical Student Status x Experience |

5.1 |

1 |

0.024 |

259 |

|

School (Arts and Sciences vs. Engineering) x Social Life |

4.65 |

1 |

0.031 |

375 |

|

Gender x Personal Growth |

4.25 |

1 |

0.039 |

361 |

|

Race x Experience |

4.24 |

1 |

0.039 |

360 |

|

Pre-Medical Student Status x Professional and Post-Grad Plans |

4.23 |

1 |

0.04 |

259 |

|

Race x Extracurriculars |

3.89 |

1 |

0.049 |

360 |

How Are Students’ Success Definitions Related to Well-Being?

To address our third and final research question of whether students’ conceptualizations of success related to their subjective well-being, we conducted a set of bivariate correlations between themes present in 10% or more of students’ success definitions and their well-being. Descriptive statistics and demographic differences in well-being are available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/be6fr/?view_only=c5193320649f4c2a8b2b268a4f890621).

Students who scored higher on well-being were significantly more likely to mention Intellectual Growth (e.g., learning, being challenged, determining academic interests), r (374) = .10, p < .05, and significantly less likely to mention Balance (e.g., well-roundedness, requiring multiple types of success), r (374) = −.11, p < .05, in their definitions of success in college. No other correlations between success definition themes and well-being were significant.

Discussion

The goals of the present study were to evaluate how undergraduate students define success in college, how conceptualizations of success vary across individuals, and how they predict well-being. We focused specifically on students at a private, selective university because of the unique pressures to excel that are present in these settings. In the sections that follow, we summarize the novel findings generated by this approach and discuss implications of these findings for educators, as well as limitations and future directions for this work.

Students on a Selective Campus Define Success in Multifaceted Ways

When asked to “Define what success in college means to you,” academic (e.g., good grades, GPA, classroom achievement, dean’s list, getting degrees) and social (e.g., social life, friendships, relationships) aspects of success were the most common themes in students’ definitions, each present in more than half of responses. Put simply, college students consider both social life and academics to be primary in their definitions of success, consistent with the “work hard, play hard” mentality emphasized at many selective university campuses.

Although social and academic themes were the most common, we found that students’ definitions of success were variable and multifaceted, confirming the notion that there is no single definition of college success (Horton & Snyder, 2009; Jennings et al., 2013; Yazedjian et al., 2008). Participants’ responses typically included at least three major themes, with some students mentioning up to nine themes. Consider this response, for example:

“To me, success in college means a well-balanced academic, extracurricular, and social life. This means maintaining my emotional and mental wellbeing while achieving the most I can in my college coursework and extracurricular activities. I want to center my experiences on getting exposure to interesting ideas and challenge myself. I hope to exit college without regrets and achieve my career and future goals.”

The variety of themes in definitions like this one shows that students value many criteria for success beyond academics and grades. Although the inclusion of multiple themes in students’ success definitions might reflect a belief that success requires balance, we did not find any significant relationships between the number of themes participants mentioned in their responses and the inclusion of Balance (or any other theme) in their definitions. The presence of many themes in success definitions may instead reflect high value placed not on balance, per se, but on well-roundedness. Our expectation that themes related to academic achievement (represented by Academic Performance, present in more than 52% of responses) would be more common than themes related to academic engagement (represented by the Intellectual Growth theme, present in nearly 31% of responses) was also confirmed.

Success Definitions Vary With Goal Orientation and Academic Motivation

Our findings suggest that students’ understanding of success is connected to differences in goal orientations and academic motivations. For example, the Experience theme (e.g., trying new things, having no regrets or a meaningful/fulfilling college experience) was positively correlated with mastery orientation (looking to gain knowledge and skills) as well as with the most intrinsic form of motivation: intrinsic motivation to know. These findings are consistent with various conceptualizations of intrinsic motivation as perceiving activities as a goal, rather than a means to a goal (Fishbach & Woolley, 2022; Ryan & Deci, 2020). The Experience theme was negatively correlated with the two most extrinsic types of motivation: introjected regulation and external regulation. Similarly, the Future-Readiness theme (e.g., preparedness to handle life after college, world perspective) was negatively correlated with both performance orientation (a focus on outperforming peers) and the most extrinsic type of motivation: external regulation. Taken together, these findings suggest that definitions of success mirror differences in motivation.

We also noted a positive relationship between introjected regulation (e.g., being motivated by a tangible, self-enforced outcome) and the themes of Extracurriculars (e.g., clubs, charity work, athletics, research, leadership positions, other student organizations) and Balance (e.g., well-roundedness, requiring multiple types of success) in definitions of success. Students high in introjected regulation may set their own tangible goals in various silos of college life and believe that accomplishing all or most of these goals is important to being successful. Together, these findings suggest that students’ different motivations connect to varied conceptualizations of success in college. Various success definitions may shape student choices and behaviors in ways that, in turn, affect their academic achievement and college experience.

Success Definitions Vary Across Demographic Characteristics

Students’ definitions of success varied not only as a function of differing motivations, but also based on demographic differences, such as class year. Juniors were the most likely and first years the least likely to mention Professional and Post-Grad Plans (e.g., acceptance to post-graduate programs or prestigious/high-paying internships and jobs). Students who complete summer internships in business have been found to get significantly more post-graduation job offers (Gault et al., 2010), and in the authors’ experience, many students at this university seek summer internships between their junior and senior year in hopes of securing future employment. We suspect this leads many juniors to focus on this theme in how they view success. Seniors did not mention professional and post-graduation plans as much as juniors. Given how close the seniors are to graduation, this finding was surprising and may reflect the relatively small number of seniors in the sample or capture the shifting priorities between years. First-year undergraduates likely experience less pressure to iron out details of their post-college lives and are thus less likely to mention professional and post-graduation plans when discussing success in college.

We also found that characteristics related to the curriculum and activities students choose to pursue predicted different conceptualizations of success. For example, students enrolled in the arts and sciences school are more likely to define success in terms of both Social Life (e.g., social life, friendships, relationships) and Academic Performance (e.g., good grades, GPA, classroom achievement, dean’s list, getting degrees) than their counterparts in the engineering school. These differences might reflect different cultures in these schools that shape how students think about success, or perhaps different admissions strategies that select for different sorts of students.

NCAA student-athletes were more likely to mention the theme of Extracurriculars, referring to sports specifically, in this case, in defining success, showing that athletic success is essential to their conceptualization of overall college success. NCAA student-athletes were also more likely to define success in terms of Academic Performance than non-athletes, which may reflect the unique pressures student-athletes experience to excel both in sports and as students. Student-athletes grapple with negative stereotypes regarding their academic abilities (Riciputi & Erdal, 2017), which may lead them to focus more on proving themselves academically. Consider the definition of success from this student-athlete, who described wanting to “Get grades that I am proud of, that put me in the top tier of student athletes. I’d like to be seen as a good student, not just a good student athlete.” Furthermore, student-athletes may be motivated to reach academic success to fulfill NCAA requirements—earning at least six credits each term, meeting milestones in progress towards their degrees, and achieving their institution’s minimum GPA required for graduation by their fourth year—for eligibility to participate in NCAA athletics (National Collegiate Athletic Association, n.d.).

Pre-medical students were more likely to mention Professional and Post-Grad Plans (e.g., acceptance to medical school) than non-pre-medical students. One pre-medical student wrote: “[success] means attaining a high GPA, high MCAT and enough extracurriculars to get me to med school while not going insane and being alone.” At the same time, pre-medical students’ emphasis on Experience (e.g., trying new things, having no regrets or a meaningful/fulfilling college experience) suggests that they seek to make the most out of what college has to offer, perhaps to maximize enjoyment and to build a strong medical school application.

Success definitions also varied with aspects of student identity like gender. Students who identified as men were less likely to mention Personal Growth (e.g., maturing, learning about oneself, becoming a better person, stepping out of comfort zones) and Intellectual Growth (e.g., learning, being challenged, determining academic interests) than those who identified as women. This supports past research on men and women’s differing success definitions (Dyke & Murphy, 2006) and values in the workplace. Men have more instrumental work values like security and benefits; women are more likely to hold affective values like personal growth and meaningful work (Elizur, 1994).

Students with traditionally marginalized identities expressed definitions of success that differed from their non-marginalized peers. For example, students from racial minority backgrounds (primarily Hispanic/Latino and Black/African American in this sample) were less likely to define success in terms of Social Life (e.g., social life, friendships, relationships), Extracurriculars (e.g., clubs, charity work, athletics, research, leadership positions, other student organizations), and Experience (e.g., trying new things, having no regrets or a meaningful/ fulfilling college experience) than their White and Asian peers. This is consistent with past findings that marginalized students are less likely to participate in extracurriculars and have lower expectations for social relationships in college (Martin, 2012). These differences may suggest that the negative stereotypes and barriers to achievement these students tend to experience (e.g., Henry, 2006) affect how they think about success in college.

First-generation students, who also tend to experience various barriers to success in college, were more likely to conceptualize success using Individualized Goals (e.g., achieving personally defined goals or standards, being proud) compared to continuing-generation students. One FG student wrote: “Success is achieving a long-term goal that makes you happy.” Because FG students often lack family support and knowledge of what to expect from college (Pascarella et al., 2004), they may feel they have to define college success on their own.

International students, who often experience language-based and cultural barriers to social success (Andrade, 2006), were more likely than non-international students to consider Social Life (e.g., social life, friendships, relationships) a facet of success. For many international students, inclusion of this theme may reflect specific concerns about fitting in socially or cultural differences they come to college with. Together, these findings suggest that success definitions may be shaped by the cultures students come from and engage with on campus, as well as their specific interests and obstacles. Knowing which demographic groups are more likely to define success in particular ways can be valuable for future research and potential interventions.

Success Definitions Are Linked to Well-Being

Previous literature (Gill et al., 2021) indicates that internally defined criteria for success tend to be associated with higher well-being. This connection was supported in the present study. Defining success as Intellectual Growth (e.g., learning, being challenged, determining academic interests) was linked to higher satisfaction with life, suggesting that students who are more focused on learning, finding academic direction, and gaining knowledge are generally more content. Notably, most students (69%) did not mention Intellectual Growth in their definitions of success. This disconnect between the most common way and the potentially healthier way to operationalize success in college highlights an opportunity to change discourse around success and to work towards improving students’ well-being. Surprisingly, those who scored lower in well-being were more likely to mention the Balance theme (e.g., well-roundedness, requiring multiple types of success). One interpretation is that students who emphasize “balance” may put more pressure on themselves to achieve success in many ways, potentially increasing stress and other negative emotions. This interpretation is supported by prior findings that students at selective universities report feeling pressure to be well-balanced (Kerrigan et al., 2017). Alternatively, students experiencing lower well-being may emphasize “balance” in their conception of success because they realize they are neglecting certain domains of life.

Ultimately, our findings emphasize that students’ definitions of success at a highly selective university are multifaceted, extending far beyond good grades to include social life, professional and post-graduation plans, and more. Students in our sample think about college success in personal ways, as demonstrated by the relationships we identified between success definition themes and individual differences in goal orientation, academic motivation, demographic characteristics, and well-being.

Implications for Practice

The present findings offer useful insights for all who support student success in a university setting, including administrators, advisors, and faculty. Given that particular definitions of success (those regarding intellectual growth, for example) are related to higher well-being in college, administrators might encourage orientation programming for new students that encourages healthy conceptualizations of success on campus. Faculty can reinforce these conceptualizations in course objectives and assignments to create a consistent message to students about what success means in the classroom. On a larger scale, curriculum and graduation requirements might be adjusted to reflect a stronger emphasis on multifaceted success and personalized growth that may lead students to greater intellectual fulfilment. For example, the major declaration process might include opportunities for students to reflect on how a particular path of study will serve personally identified and valued aspects of success.

Given that each student in our sample defined success in a unique way, but also in ways that were related to social identity, academic advisors might engage in conversations with students about how they, as individuals, conceptualize success, how their conceptualizations relate to their backgrounds and social identities, and how those conceptualizations guide their choices and satisfaction with their lives. Advisors can play an important role in guiding students’ decisions—from course selection to post-graduate pursuits—with reaching success in the most personally meaningful way as a grounding factor.

For the institution at which this research was conducted, students were most likely to define success in terms of social life, academic performance, future-readiness, professional and post-graduation plans, and personal growth. With this knowledge, adults on campus can support students as they pursue those specific aspects of success. Advisors can help students identify personal, social, and academic goals and track their progress towards specific benchmarks for each domain during regular check-ins. Similarly, the career center can host group and individual sessions to help students feel in control of their readiness for navigating careers and the adult world on their own after graduation.

Implications for Future Research

Our project had several limitations that inspire directions for future research. The present study focused on students’ definitions of success, in their own words, in response to a simple question. Participants may have offered definitions that reflected too little detail, too little thought, or a desire to present themselves in a positive light to the researchers. Participants also likely varied in how adequately they could express their definitions of success in words. Although our approach allowed us to capture a broad range of definitions of success from different students, future research might build on these findings with more extensive interviews with students about success or measure social desirability (e.g., Crowne & Marlowe, 1964) to determine which participants responded dishonestly. Future studies might further validate the themes identified in the present study by examining whether they predict students’ actual behavior, in the laboratory or real-world context. Future work might also examine students’ conceptualizations of success without requiring them to express their definitions in words; for instance, students could evaluate pre-written definitions of success to reveal what themes they personally align with.

Although we worked to recruit a diverse sample from one college campus, a large proportion of our respondents were students enrolled in introductory psychology. Given our findings that students may think differently about success in different disciplines (i.e., arts and sciences vs. engineering), future studies might recruit students more systematically across disciplines. Future work might also extend these findings to similarly selective and less selective universities to gain deeper insight on how success definitions compare in different settings.

Our findings regarding differences in conceptualizations of success by demographic characteristics also merit further exploration. Future studies might investigate how students with racial minority backgrounds experience college differently based on their lower likelihood to consider social life as an aspect of success. Similarly, future research about the links between balance, success, and well-being would provide a deeper understanding of this complex and important relationship.

A long-term goal of this project is to lay the foundation for future interventions that might shape students’ perceptions of success in ways that will promote well-being, a more satisfying college experience, and higher achievement. For example, if conceptualizing success as Intellectual Growth (e.g., perception that most students mention learning, academic direction in their definitions) truly amplifies well-being, then interventions might boost well-being by helping students frame success as learning and exploring academic interests. Future projects should go beyond the descriptive and correlational approach in the present study to establish causal relationships between students’ success definitions and other outcomes.

To conclude, the present research provides new insight into what success means to students enrolled at a selective university, who experience unique pressures to excel in multiple aspects of college life. Our findings suggest that students’ goal orientation, academic motivation, and various aspects of their interests and identities predict how they conceptualize success, adding to previous research that has connected individual differences to measurements of success itself. Links observed between themes in students’ success definitions and their well-being hint at future opportunities to enhance well-being by changing students’ conceptualizations of success. We hope the present findings will inform researchers and educators working towards the long-term goal of improving students’ well-being and experience.

1 The two items reflecting intrinsic motivation to experience stimulation were revised from the standard statements to broadly capture students’ experience, avoiding the focus on pleasure obtained from reading particular authors’ work present in the original item.

2 55.9% of students identified as female, 1.9% identified as non-binary/third gender, 0.6% identified as both female and non-binary/third gender, 0.3% identified as both male and transgender, and 0.3% preferred not to say their gender identity. For simplicity, these participants were grouped together in our analyses.

References

Andrade, M. S. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(2), 131–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240906065589

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1964). The approval motive: Studies in evaluative dependence. Wiley.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Dyke, L. S., & Murphy, S. A. (2006). How we define success: A qualitative study of what matters most to women and men. Sex Roles, 55(5–6), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9091-2

Elizur, D. (1994). Gender and work values: A comparative analysis. The Journal of Social Psychology, 134(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1994.9711383

Fishbach, A., & Woolley, K. (2022). The structure of intrinsic motivation. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9(1), 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-091122

Gault, J., Leach, E., & Duey, M. (2010). Effects of business internships on job marketability: The employers’ perspective. Education + Training, 52(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011017690

Gill, A., Trask-Kerr, K., & Vella-Brodrick, D. (2021). Systematic review of adolescent conceptions of success: Implications for wellbeing and positive education. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1553–1582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09605-w

Henry, P. (2006). Educational and career barriers to the medical profession: perceptions of underrepresented minority students. College Student Journal, 40(2), 429–441.

Horton, B. W., & Snyder, C. S. (2009). Wellness: Its impact on student grades and implications for business. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 8(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332840802269858

Jennings, N., Lovett, S., Cuba, L., Swingle, J., & Lindkvist, H. (2013). “What would make this a successful year for you?” How students define success in college. Liberal Education, 99(2).

Jo, E., Lee, M., & Lee, W. (2021). Influence of early adolescents’ mastery goals on inter- and intra-individual relationships between metacognitive monitoring and academic outcomes. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 41(8), 1203–1227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431621989815

Kerrigan, D., Chau, V., King, M., Holman, E., Joffe, A., & Sibinga, E. (2017). There is no performance, there is just this moment: The role of mindfulness instruction in promoting health and well-being among students at a highly-ranked university in the United States. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 22(4), 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587217719787

Kotera, Y., Conway, E., & Green, P. (2021). Construction and factorial validation of a short version of the Academic Motivation Scale. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2021.1903387

Martin, N. D. (2012). The privilege of ease: Social class and campus life at highly selective, private universities. Research in Higher Education, 53(4), 426–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-011-9234-3

National Collegiate Athletic Association. (n.d.). Staying on track to graduate. Retrieved March 11, 2023, from https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2021/2/10/student-athletes-current-staying-track-graduate.aspx

Naylor, R. (2017). First year student conceptions of success: What really matters? Student Success, 8(2), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v8i2.377

Pascarella, E. T., Pierson, C. T., Wolniak, G. C., & Terenzini, P. T. (2004). First-generation college students. The Journal of Higher Education, 75(3), 249–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2004.11772256

Riciputi, S., & Erdal, K. (2017). The effect of stereotype threat on student-athlete math performance. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 32, 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.06.003

Roedel, T. D., Schraw, G., & Plake, B. S. (1994). Validation of a measure of learning and performance goal orientations. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 54(4), 1013–1021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164494054004018

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Senko, C. (2019). When do mastery and performance goals facilitate academic achievement? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 59, 101795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101795

Stewart, M., Stott, T., & Nuttall, A.-M. (2016). Study goals and procrastination tendencies at different stages of the undergraduate degree. Studies in Higher Education, 41(11), 2028–2043. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1005590

Travers, C. J., Morisano, D., & Locke, E. A. (2014). Self-reflection, growth goals, and academic outcomes: A qualitative study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12059

Urdan, T., & Kaplan, A. (2020). The origins, evolution, and future directions of achievement goal theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101862

Yazedjian, A., Toews, M. L., Sevin, T., & Purswell, K. E. (2008). “It’s a whole new world”: A qualitative exploration of college students’ definitions of and strategies for college success. Journal of College Student Development, 49(2), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2008.0009