Men of Color: First-Year Students Attending a Predominantly White Two-Year Institution

Patrick E. Turner*

New Mexico State University

Abstract

The retention and degree attainment rate of men of color (MOC) remain pressing issues, particularly for those attending predominantly White community colleges in the United States. Though 62% of MOC begin their academic journey at a two-year institution, only 25% graduate with a degree or certificate within three years (Hilton et al., 2012; Huerta et al., 2021; Mangan, 2014). The first year of college can be challenging, especially for those students belonging to an underrepresented, underserved, low-income, or first-generation population. Unfortunately, MOC encounter confounding issues that serve as barriers to their overall academic and social success. Aside from having to navigate those challenges typically associated with the first year transition, MOC face additional issues related to race, gender, and masculinity (Huerta, et. al, 2021; Williams et al., 2014). Some of these issues prevent MOC from being seen as total human beings, but as generic persons reduced to labels and stereotypes (O'Neil, 2015). There exists a need for further research that explores the first year experience of MOC. Comprehending this critical juncture of their academic pathway could lead to constructing multilayered interventions at the student and institution level.

Introduction

Over the past few years, research has shown a steady increase in the college enrollment of men of color (MOC; National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2019b). However, colleges and universities struggle with the low retention, persistence, and graduation rates of minority groups, particularly MOC (Espinosa et al., 2019; NCES, 2019a). For this study the descriptors men and male are used interchangeably which is common for this scholarship. In the 2008 article, Colleges Seek Key to Success of Black Males in the Classroom, the author argued that the issue for postsecondary institutions is not having ample knowledge of best practices that support students of color. Instead, the problem lies in offering educational leaders the right incentive or "carrot" to act on that knowledge (Schmidt, 2008). The racial and ethnic profile of students enrolled in American colleges and universities has drastically changed over the last 20 years, shifting from a predominantly White population to an increasingly more racially and socioeconomically diverse global community (Espinosa et al., 2019). Since 1976, the number of students of color (i.e., Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Black) attending college has grown, while the enrollment of White students has declined from 84% to 57% (NCES, 2019b). The dramatic change in student profile comes with a variety of challenges and opportunities for both the institution and the student (Seidman, 2012).

According to the College Board (2010), one major challenge is eliminating the educational disparities and achievement gaps that exist for low-income students and individuals belonging to a racialized or minority group. On the surface, the increase in enrollment seems promising, but the numbers paint an inaccurate picture of the educational experience and degree attainment for men of color. The educational achievement of MOC demands a closer examination from educational leaders, policymakers, philanthropists, and community leaders (College Board, 2010). Though two-year colleges are the starting point for 62% of MOC, only 25% graduate with a degree or certificate within three years (Hilton et al., 2012; Mangan, 2014). According to the National Center for Education Statistics (2019b), 27% of Native American, 27% of Hispanic, and 22% of Black male students graduate with a degree or certificate within 150% of normal time, compared to 33% of White male students. For various reasons, MOC prematurely leave college without the institution having a clear understanding for their departure. Instead of leveling the playing field, a possible solution may be restructuring the landscape to ensure equity in educational access, support, and degree obtainment.

Literature Review

The problems postsecondary institutions have with educating, retaining, and graduating MOC have been featured news (Harper & Harris, 2010). With an increased emphasis placed on men's issues at the government, philanthropic, and national level, there should exist an awareness of the gender gap in degree attainment and college enrollment. In 2014, President Obama's administration launched the My Brother's Keeper Initiative to increase the number of MOC that complete a postsecondary degree through mentorship, skill development, and support networks (The White House, 2014). A disaggregation of the data by gender, race, and institutional sector reveals a wider gap for males attending a community college, compared to those at four-year institutions (Briscoe et al., 2020).

During the late 1970s, male students represented a slight majority of college-enrolled students; however, both males and females attended colleges and universities almost at equal rates (Field, 2021; Harper & Harris, 2010). In 1976, the U.S. Department of Education reported that males accounted for 52% of undergraduate enrollment, while females represented 48%. By 1980, females accounted for 52.3% of degree seekers, while males started slowly disappearing from the college environment and educational pipeline (Harper & Harris, 2010). According to Field (2021), several reasons exist for the gender imbalance, but the underscoring explanation points to differences in academic, social, and economic expectations. Academically, females outpace males in primary and secondary schooling and are more inclined to reach out for assistance when facing problems. Additionally, males experience a higher level of social pressures to enter the workforce to assume the role of family provider (Field, 2021).

By 2008, females accounted for 56.9% of undergraduate students, sparking concerns about the enrollment, retention, and degree attainment of male students (Harper & Harris, 2010). Overall, research has shown a decline in the retention and graduation rates of males in all racial groups, but the largest attrition rate was amongst MOC (Harper & Harris, 2010; Huerta et al., 2021). Data from the National Center for Education Statistics (2020) revealed the enrollment of MOC not only fell behind that of White males, but also women of color. In 2016, among males, the enrollment rate was 48% Asian Americans, 47% for Native Americans, 42% for Hispanic, 42% for Pacific Islander, and 38% for Black, compared to 45% of Whites (de Brey et al., 2019; Espinosa et al., 2019). In 2017, a status report on race and ethnicity in higher education was published by the American Council on Education. According to the report, 19.8% of Pacific Islander, 15.2% of Black, 12.4% of American Indian and 11.4% of Hispanic males obtained a bachelor's degree in 2017, compared to 23.6% of White males (Espinosa et al., 2019). Despite the growing enrollment at postsecondary institutions, MOC account for less than 20% of four-year college degree holders (NCES, 2020).

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this qualitative case study was to explore the factors that act as supports or barriers to the academic success for MOC during their transition into a predominantly White two-year public college. The voices of MOC are often silenced, marginalized, or misunderstood instead of serving as a resource for program development or redesign of intervention measures. Personal narratives and stories provide a contextual framework that paints a clear picture of the complexities of the lived experience (Hilton et al., 2012). The purpose of this case study was to shine a spotlight on a shadowed and misunderstood population. The hope is that findings from this research will inform policy decisions regarding educational equity, social mobility, and social justice for MOC.

Method

Theoretical Framework

Tinto's 1975 student integration model (SIM) and the male gender role conflict (MGRC) by James O'Neil served as the framework for the study. Both models provided critical and in-depth insight into the psychological, sociological, and psychosocial state of male students during their transition into the social and academic environment of a predominantly-White two-year college. The theories reveal the nuanced and complex environmental factors that influence the cognitive, non-cognitive, emotional, and relational state of male students while navigating the college environment.

Vincent Tinto's Student Integration Model . Tinto's model examines student integration and retention through the discipline of social psychology. The college experience encompasses the social and academic atmosphere shaped by the educational institution environment. The decision of a student to persist or dropout is determined by the level of congruence or incongruence between individual attributes and institutional culture, often referred to as "institutional fit" (Tinto, 2012). Drawing on the work of Arnold Van Gennep and Emile Durkheim, Tinto posited that the integration of students relies on the progression through three different phases, not necessarily in sequential order. The associated experiences with each phase can vary by degree and timeframe. A seamless integration entails (a) detachment from past communities, (b) transition between communities, and (c) assimilation into the new college community (Seidman, 2012; Tinto, 2012). The level of engagement, commitment, and belonging depends heavily on the connection fostered between the student and the institution (Seidman, 2012). This interrelationship determines whether the student will persist or prematurely leave the institution without completing a degree or certificate. The highest point of vulnerability is at the early stages of college when the student has not fully integrated or committed to the institution (Tinto, 2012). Competing social, financial, family, and academic influences have the greatest impact during this period (Tinto, 2012). Institutions can take proactive measures by providing early support, conducting outreach campaigns, and offering intentional assistance. These measures can be both formal and informal and take place inside or outside the classroom.

Male Gender Role Conflict (MGRC) . MGRC is a socialized construct that assigns restrictive gender roles. The roles limit agency and human potential while having a negative psychological impact on human development (O'Neil, 2015). Conflict emerges from the inflexibility and expected behaviors of males, typically associated with machismo, athleticism, sexual prowess, restricted emotions, and social responsibilities. The negative consequences of the sexist assumptions result in a decline of emotional maturity, confinement of personal capabilities, and the devaluing of the self and others (O'Neil, 2015). According to O'Neil, the greatest misfortune of MGRC is the loss of development opportunities, agency, and reaching of full potential.

Male Gender Role Conflict (MGRC) can have negative consequences for both the individual and others due to the restrictive and compartmentalized roles imposed on males (O'Neil, 2015; Wester, 2008). The expected behavior can sometimes be inconsistent or incompatible with what a particular situation requires (Wester, 2008). For example, an issue may require a level of vulnerability or sensitivity that the male may feel incapable or uncomfortable displaying which can lead to unsuccessful outcomes. Six patterns of conflict have been identified that can be problematic for males, if not effectively managed: (a) restrictive emotionality, (b) health care problems, (c) obsession with achievement and success, (d) restrictive sexual and affectionate behavior, (e) socialized control, power, and competition issues, and (f) homophobia. Contextually, these patterns influence the lived experience of males and vary depending on intersecting identities such as race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. The theory of MGRC is both fluid and adaptive to various identities and social junctures (Wester, 2008).

Research Question

To understand the factors that are important to MOC and that shape their college experience, one overarching research question was posed: How do men of color (i.e., Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans) reflect on their college experience attending a predominantly White two-year college?

Institution

The study was conducted at a small open-access public two-year college located in the northwest region of the United States. The pseudonym "Mountain College" was used to protect the identity of the college. The estimated enrollment was 1,500 students with degree offerings of Associate of Arts, Associate of Sciences, Associate of Applied Science, and Certificate of Applied Science. The racial and ethnic makeup of the student population was 90% White, 3% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 1% African American, 1% Hispanic, and 4% Unknown/Not Reported, which was reflective of the broader demographics of the state. The enrollment capacity of Mountain College was 70% part-time and 30% full-time, with an average student age of 23 years, 34% identified as first-generation, and 45% were Pell eligible. The majority of the students were from small rural areas or tribal reservations where farming and ranching were the main employment industries.

Participants

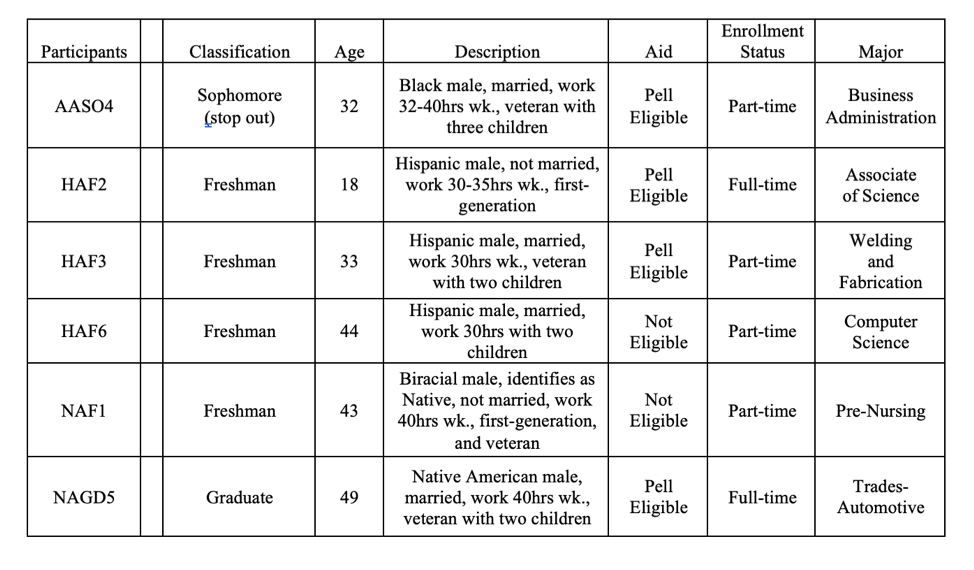

The male participants represented diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds to capture the nuanced and complex details of the lived experience. Participants consisted of two American Indian/Alaskan Native students, three Hispanic students, and one African American student. The study used a purposeful homogenous sampling approach because the informants identified as male and attended the same college (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). A purposeful sampling technique is appropriate when participants possess similar or identical characteristics. Additionally, the males were able to provide first-hand accounts, which placed their lived experience in context, which was an essential component of the study (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). Classified by college enrollment status for the 2017-2018 academic year, the sample consisted of four currently enrolled freshmen, one sophomore stopped-out, and one recent graduate. With an average age of 37 years, five males identified as non-traditional students (i.e., 26 and older) and one as a traditional student (i.e., 18-25). The racial demographics and profile of research participants (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics and Profile of Research Participants

Data Collection and Analysis

Institutional Review Board approval was granted by the parent institution, which oversees the two-year college. A request for directory information (e.g., name, address, phone number, and campus email) of all currently enrolled and non-returning male students was submitted to the Vice President of Student Affairs and Information Service & Technology. The report consisted of 312 male students, of which 11 identified as MOC (i.e., Black, Native American, and Hispanic). An email was sent to each of the 11 males explaining the purpose of the study and an invitation to participate. Of the 11 males, six expressed an interested in the study.

Interviews were scheduled around the academic, personal, and work schedules of the participants. Two interviews had to be conducted after regular business hours and on the weekend due to a limitation on the participants’ time. Since the interviews were audio recorded, participants were required to sign a consent form granting permission. Informants answered 23 semi-structured open-ended questions covering various aspects of the college experience including challenges, opportunities, fears, peer groups, support network, masculinity, gender role, belonging, and faculty-student relationships. The questions allowed participants to provide detailed accounts of their lived experiences while attending the predominantly-White institution. Interviews lasted approximately 60-70 minutes depending on the level of details provided by the participants.

Participants were identified according to their race (i.e., B-Black, HA-Hispanic, and NA-Native), classification (i.e., F-freshman, S-sophomore, SO-stop out, and GD-graduated), and an assigned number. For example, a Hispanic freshman who was first to be interviewed would be coded HAF1. The qualitative software NVIVO 12 was used to systematically isolate, track, and sort patterns. Both the audio recordings and transcripts were uploaded to create files, cases, case classifications, and codes. Cases are units of analysis (e.g., person, place, etc.) created to categorize data, whereas codes are identified themes and patterns (Jackson & Bazeley, 2019). A predetermined coding system of words, phrases, sentiments, similar statements, ideas, and topics served as the benchmark. Six broad codes and 30 themes and patterns were identified and labeled as major or minor. Major "themes and patterns" were ideas or topics expressed by 60% or more of the participants. The significance of a theme or pattern went beyond merely the counting of words, which can limit comprehension if not placed in context. The social and academic realities of the participants were placement in a scientific, yet personal and authentic context (Denzin, & Lincoln, 2011).

Results

Several major themes surfaced that influenced the first year college experience for MOC attending a predominantly White two-year college: cultural competency and humility, belonging, masculinity and identity, and outreach and support. These themes functioned both independently and interdependently to shape the academic and social integration of MOC into the college environment.

Cultural Competency and Humility

Cultural competency and humility, defined as having the ability to recognize and comprehend cultural differences and similarities, was a critical factor. This includes the ability to integrate the knowledge into a practical, sensitive, and respectful manner (Greene-Moton & Minkler, 2020). The lack of cultural competency and humility was cited by 100% (n = 6) of the participants as a challenge during the first year attending the institution. Participants expressed concerns that faculty and administrators lacked the education, training, and sensitivity to address cultural issues or the understanding of the impact that culture has on the classroom experience. The frustration heard in the voice of participant NAGD5 expressed how good intentions are harmful if not supported by education, research, and sensitivity:

The college decided to celebrate Native American week by plastering black and white pictures all over the school walls of Native students standing in front of boarding schools. As if we want to celebrate that time of oppression and assimilation. We were considered animals and savages to them that needed to be tamed, which only the White man could do. The saying was “kill the Indian, save the man”. I found out the diversity committee group was five White people and one Asian woman. I was f**king angry that a college could be so ignorant.

The belief was that a greater understanding of the realities of racialized, marginalized, underserved, and underrepresented groups, particularly students of color, was vital. Students who are often first-generation and from low-income neighborhoods or reservations sometimes are academically unprepared or underprepared and lack the social capital to adequately navigate the college environment. The entry point for many of the males was through non-traditional academic pathways. Three of the participants were military veterans (e.g., honorable and dishonorable discharged). One of the veterans, later diagnosed with Posttraumatic Syndrome (PTSD), involuntarily separated from the military for disciplinary issues. Another participant admitted to having a criminal record for drug possession and domestic violence, which led to multiple police arrests. According HAF3, his initial college orientation was challenging:

Coming to college. I am Hispanic, convicted felon, tatted up with a criminal record, so it was, at first, I felt like it was kind of an automatic judgment. I don't think they should look at you for things you've done in the past or race, but what you're doing now and what you're trying to achieve now. People do change, and so do circumstances.

The respondents understood the responsibility of the institution was to ensure the safety of students, but hoped some level of compassion, empathy, and awareness would extend to MOC, especially if the student possessed a criminal record, suffered from PTSD, or wore sleeves of visible tattoos. Institutional policies and practices should reflect an awareness of culture and gender, which participants felt was absent. Participant HAF6, an undocumented immigrant, felt hesitant about filling out official admission paperwork, answering personal questions, or reaching out for assistance in fear of deportation or endangering his family.

You have this political system now that when you have an accent and somebody asks you directly where you're from there is no way, no way you're going to tell them where you're from, where you're originally from because of it. And if you made a mistake at telling everybody where you're from and all that kind of stuff, yeah, what if that person calls somebody else and, Hey, we have somebody with an accent here in college then you are gone. I don't know that, so I don't want to talk to nobody.

According to Greene-Moton and Minkler (2020), a misconception among academic professionals is that cultural competence and cultural humility are interchangeable concepts without a distinct difference. This mindset has been associated with the White culture, which presents the false appearance of diversity and inclusion. Lacking is the presence of empathy for the social realities of people of color, which leads to misunderstandings, stereotypes, marginalization, distrust, and sometimes death (Greene-Moton & Minkler, 2020).

Beyond “Welcome” to a Sense of Belonging

The inability of the institution to foster a sense of belonging was viewed by approximately 85% of participants (n = 5) as a major issue. According to Strayhorn (2012), a sense of belonging refers to whether or not an individual feels valued, respected, and empowered, and matters to the organization. This entails having one's voice included in the forward direction and daily operation of the organization. In the college environment, the integration and celebration of cultures, expressions, and experiences of students cultivates belonging. Integration must occur at the systemic level of the institution, which is inclusive of policies, procedures, curriculum, and pedagogy, to permeate the broader institutional structure.

When asked if they felt “welcome” at the college, participants felt the campus was warm safe, and accessible. An accessible campus means students are permitted or admitted willingly into a situation or environment, which is a general extension of social courtesy. However, on a few occasions, some of the participants overheard micro-aggressive and racially incentive comments made by faculty, students, and administrators that caused some uneasiness or anger. To avoid unwanted attention or trouble, ignoring or suppressing the frustration was the best option. Participant NAF1, who identified as biracial (i.e., White and Native American), detailed his experience:

I was told I got the best of both worlds because I'm a tribal member but I look like a Wasi'chu (i.e., people of European descent). I hear some of the stereotypical stuff you hear about Indians. You hear comments about, "Indians get everything for free." They got free hospital, they get free money... you know? Why did the Indians get free college? I just ignore and keep going. Ignore the ignorance.

According to Strayhorn (2012), the search for a connectedness with other people and communities is a basic and intrinsic human desire. The absence of that oneness can have a negative impact on the behavior and performance of a student. This includes the mental health and psychological well-being of the person, which directly affect academic performance. At least 67% (n = 4) of the participants experienced overwhelming feelings of isolation, disconnectedness, and (in)visibility. Participants expressed moments when classroom peers purposely avoided interacting with them during class activities. Faculty members, in fear of creating an uncomfortable atmosphere, avoided conversation about race and race relations. Participants struggled to find a balance embracing their own racial identities within a majority White student population. W. E. B. Du Bois referred to this internal conflict as "twoness". Twoness is the internal psychological struggle between two warring identities, within a single person, particularly people of color (Itzigsohn & Brown, 2015). An example would be recognizing ones Native American heritage, while also being considered an American. The two identities sometimes have conflicting ideologies and belief systems which the individual has to navigate.

The institution established a welcoming environment, but not an atmosphere that promoted belonging. Unfortunately, a gesture of welcome only requires an extension of a social courtesy and involves minimal effort. The MOC believed belonging called for inclusive, intentional, and long-term sustainable actions. This type of engagement and validation is not instantaneous, but necessitates extensive and systemic planning. Targeted and intentional actions are vital to the ongoing lived experience, which consists of both the social and academic realities (Platt et al., 2015).

Masculinity and Identity

The idea of masculinity and identity surfaced several times during the interviews as participants described their lived experience. Sixty-seven percent (n = 4) mentioned the influence that masculinity or being considered a man had on their college experience and decision-making. Each male had a personal definition or male code that determined behaviors such as help seeking, instructor-student relationship, career choice, and communication. According to Harper and Harris (2010), males are often acutely aware of the socialized differences between the expected behaviors of males and females. Males are expected to maintain a level of emotional control, serve as the family financial provider, and avoid signs of vulnerability or weakness such as whining or crying or any behavior regarded as feminine. Participant HAF3 stated:

Having a family, I guess I felt more pressured on making sure the family is taken care of first over school than anything. That is because that's my primary job, in my opinion. It’s being a man.

Harper and Harris (2010) referenced MGRC to explain the challenges males encounter in the attempt to reconcile gender and identity related behaviors. MGRC occurs when rigid, sexist, and restrictive socially constructed norms are assigned to gender (O’Neil, 2015). According to Harper and Harris (2010), “[MGRC] is characterized as a negative consequence of the discrepancies between males’ authentic selves and the idealized, socially constructed images that are culturally associated with masculine” (p. 70). When unable to demonstrate or uphold those masculine behaviors, males fear that others will view them as feminine or less than a man (O’Neil, 2015). Participant AASO4 found it easier to face the consequences of possible failure than to ask for assistance from a female instructor.

For me to talk to a guy, I don't know, I feel more comfortable saying, "Hey, I have an issue here." Learning something, but going to a female ... I really don't know how to put it into words and say, "Hey, I don't understand this." So I'd try to gather it on my own. I had a female instructor and I don't know. I think I felt a little, I don't want to say embarrassed to go up and talk to her. I don't know. I am not likely to say, "Hey, I've got an issue." I would rather just take the hit.

Pressured to conform to the role of provider or head of the household, socialization of males often begins at a young age (Harper & Harris, 2010). Conforming to the socialized, yet conflicting, roles can lead to restrictive behavior, devaluation of others, and lost human capabilities (O’Neil, 2015). There exists an overwhelming pressure for males to obtain an appropriate manly degree and secure a well-paying job in particular fields to promote a socially constructed image and ideology. Whether right or wrong, several of the participants admitted that being regarded as a man factored into their degree and career choice.

Proactive Outreach and Support

The transition into the college environment is a major adjustment for most freshmen. Research has shown that a large percentage of first-generation and students of color enroll in college lacking the necessary social and academic capital, which act as an additional barrier to their overall success (Postsecondary National Policy Institute, 2021). Students are leaving familiar support systems to pursue educational opportunities to increase their social mobility, or the upward progression of individuals or families through a social stratum (Arday, 2021). Arday (2021) stated that social inequities remain woven into the fiber of the U.S educational system. Consequently, educational leaders must question the mission and purpose of their institution, in addition to conducting a close examination on serving a changing and diverse population of students. Therefore, intentional and targeted support is required to mitigate barriers to success. Proactive outreach and support was cited by 67% (n = 4) of the participants as critical to a seamless integration during the uncomfortable and difficult transitional period. In the words of NAGD5:

Growing up on a reservation, you're the minority, looked down upon and it's really hard to actually leave that area, that culture. Then to take that race stuff and go to college to try to bury yourself and all your buddies and everything telling you, "You can't do it," and when you get here there's nobody to say, "Yeah, you can do it." So there's no support group whatsoever.

Proactive outreach and support was defined as accessible, intentional, and ongoing contact by administrators, such as academic advisors, career counselors, student groups, and other units charged with connecting students to both on-campus and community resources. Participants believed that support units mainly relied on students to reach out for support prior to offering proactive assistance and direction. Instead of anticipating the possible needs of students of color attending a predominantly White college, the units were either ignorant or ignored the transitional challenges encountered by minority groups. Additionally, males often possess a negative view of help seeking which only increases the fear of failure and pressure to succeed on their own (Perrakis, 2008). Seeking support requires a level of emotional expressiveness that is inconsistent with how males are socialized (Harper & Harris, 2010). The combination of males not seeking help and the institution not conducting proactive outreach creates an opportunity gap.

Study Limitation

Conducted at one two-year public college, findings from this study may not allow for the generalization of outcomes. However, the results can inform practices, program design, and targeted support to address the specific and complex needs of MOC. In addition, the recommendations made are population specific and may not be applicable to White or Asian males. The findings can only serve as a resource tool and not as an intervention for all issues associated with the college experience. Though not generalizable, educational leaders and policymakers should evaluate the descriptive and detailed information to assess its transferability to particular institutions or organizations (Turner, 2016).

Researcher Positionality

Positionality refers to the characteristics and traits of the researcher which influence their worldview on particular issues and topics. Traits such as by race, gender, religious views, values, ideology, orientation, political affiliation, intersecting identity, and other social realities can shape their perspective (Holmes, 2020). In qualitative research, disclosure is essential as it ensures transparency, vulnerability, and honesty of the process (Holmes, 2020). I am an African-American, who identifies as male, and I have worked in higher education for over 25 years at both two-year and four-year institutions. The responsibilities of my role as the Associate Provost of Student Success is to manage, track, and analyze student access, retention, persistence, and degree attainment. My research focuses on the first year experience, particularly for students of color, with special attention paid to MOC. Additionally, I am the coordinator of a project that develops efforts to support degree attainment for MOC. It has always been my personal belief that education is the great equalizer and should be accessible to all students, no matter their race, color, social economic status, or geographic location.

Throughout my career in the U.S higher education system, it has been my personal, professional, and academic experience that the system was not designed to effectively serve and accommodate the needs of students of color. Many marginalized and racialized students, particularly MOC, do not have equal access and support to accomplish their dreams. Consequently, MOC prematurely leave postsecondary institutions without the system having a clear understanding of their departure. As a Black male, it is my opinion that institutions must develop a better understanding of this student population, both as a gender and total human being. These perspective and experiences shape and inform the depth and breadth of my research. My positionality is constantly developing, shaping, evolving, and adapting to reflect changes in higher education and the student population served. Internal and external factors influence the educational realities and social mobility of students and so must the situatedness of the researcher. My theoretical and practical knowledge is a culmination of years working directly with students, parents, and educational leaders as a frontline researcher and student-centered educator.

Discussion and Recommendations

This study provided insight into the social and academic realities of MOC attending a two-year predominantly White institution. Thoughtful and targeted interventions can result in increased retention, persistence, and graduation rates. Well-orchestrated student success efforts begin with a clear understanding of the factors that engage or disengage MOC during this pivotal academic juncture. It is imperative that colleges recognize that MOC are typically nontraditional adult learners, work 30-40 hour a week, and are often married with children. Due to limited education and resources, these students are working labor-intensive second and third shift jobs with little flexibility. Consequently, the students are mentally and physically exhausted which may result in limited focus on schoolwork and challenges in meeting deadlines for assignments. Additionally, many of the males are veterans or previously incarcerated individuals, who may suffer from PTSD or other undiagnosed mental illnesses resulting in increased anxiety. Students may find it difficult adjusting to or connecting with the traditional-aged student population. Connecting these males to the Counseling Center and/or Veteran Services is vital to developing a support network and receiving tailored care. These systems can support the academic and social transition of the males into the college community (Tinto, 2012). Ultimately, remaining at the institution or leaving without a degree or certificate is determined by the level of fit between the student and the institution and early interventions provided to these males (Tinto, 2012).

Institutions must provide ongoing training for faculty, students, and administrators on the concepts of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Training should include the impact that DEI has on areas such as the college environment, curricula, teaching and learning practices, institutional policies, student engagement, belonging, and student agency. DEI training should be mandatory and cover both a historical context and examples for practical application.

Institutions must provide ongoing training for faculty, students, and administrators on the concepts of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Training should include the impact that DEI has on areas such as the college environment, curricula, teaching and learning practices, institutional policies, student engagement, belonging, and student agency. DEI training should be mandatory and cover both a historical context and examples for practical application. Men of color are not a monolithic group, so a one-size fits all approach will not address the specific needs connected to cultural differences and intersecting identities. Gender, toxic masculinity, queerness, racism, White privilege, cultural sensitivity, disabilities, and intersecting identities are all relevant topics to unpacking and understanding issues of the MGRC (O'Neil, 2015). One recommendation is to solicit the help of the Teaching Academy to discuss inclusive pedagogy, equity-minded curricula, and strength-based instructional practices. According to Lee-Bitsoi and colleagues (2014), colleges and universities are less likely to take a strength-based approach to constructing programs and interventions for MOC, which exacerbates the problem. Present approaches do not take into consideration the assets and valuable experiences brought to the campus by that MOC. Men of Color consistently compete with persisting stereotypes and mischaracterization such as being hypersexual, angry, aggressive, anti-education, and lazy (O'Neil, 2015). These labels negatively affect their experience inside and outside the classroom environment.

Predominantly White two-year colleges should take proactive approaches to offering services, academic outreach, financial literacy, and other mechanisms to ensure that MOC connect to campus resources, as well as integrate intrusive advising to create an early plan for success. The intent of preemptive action is to mitigate potential issues that may arise, not to serve as punitive or weeding out processes. Early alert and intervention measures increase the opportunities for success and minimize the chances of failure. Additionally, proactive measures eliminate solely depending on male students to seek out support services. Research has shown that college males often view help seeking as a sign of weakness, failure, and femininity (Harris & Wood, 2013; Harper & Harris, 2010; O'Neil, 2015; Wester, 2008). Finally, identify a point of contact, preferably a male person of color, to serve as an advocate to help MOC unpack and address issues of identity and gender.

Conclusion and Future Direction

Current research on MOC attending community colleges provides a promising outlook, which in some cases paints an accurate picture. Unfortunately, this is not the reality for all MOC who often succeed despite their circumstances. Colleges and universities cannot take credit for the grit, perseverance, and determination of these men. When constructing programs, interventions, and services, there should exist a synergy and uniformity between academic and student affairs. All efforts should build, connect, and reinforce other institutional values and support resources. A single activity cannot serve as the silver bullet that solves every problem, but it can possibly remedy a certain aspect of a broader issue. Culturally and gender responsive pedagogy are essential to addressing the complex needs of MOC and creating an inclusive environment for males to thrive (Stout, 2021).

Two-year predominantly White institutions enroll a large population of nontraditional students who are at least 25 years of age, work part-time or full-time jobs, caretakers, veterans, or have delayed college enrollment a year after graduating high school. Adult students typically have external support, possess life experiences, and have clear goals, although their professional pathway may not be clear. Therefore, the approach for integrating, teaching, and engaging nontraditional adult learners differ from that of traditional aged students. Nontraditional learners require more autonomy, self-direction, experiential opportunities, and real-life application, which are critical components to constructing curriculum and instruction.

The broader implication is that the United States currently struggles with its social conscience following the death of George Floyd, Ahmad Aubrey, and Antonio Valenzuela. This moment in time necessitates the need for the voices of MOC to be heard and for their stories to be told. The senseless and inhumane death of these men, either at the hands of police brutality or White vigilantes, have opened long existing wounds rooted in systemic oppression and discrimination. Institutions of higher education have always served as a space to challenge social, economic, educational, and political issues, both on the national and international stage. Men of color are intellectual capital and resources that contribute to the innovation of college campuses and the broader community (Williams & Flores-Ragade, 2010). Intentional systemic approaches are needed to better understand and support the college experiences of MOC. Charged with a responsibility to eliminate the opportunity gap, postsecondary institutions must create equitable outcomes for marginalized, racialized, and underserved students. Students the U.S. educational system neglected to serve in an equitable manner and in some cases barred from access. Institutions must first recognize MOC as full, capable, and complex human beings and then provide targeted support to enable them to not only survive but to thrive in college.

References

Arday, J. (2021). Race, education and social mobility: We all need to dream the same dream and want the same thing. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(3), 227-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777642

Briscoe, K. L., Jones, V. A., Hatch-Tocaimaza, D. K., & Martinez, E. (2020). Positionality and power: The individual's role in directing community college men of color initiatives. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice , 57(5), 473-486. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2019.1699103

College Board. 2010. The educational crisis facing young men of color. College Board.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (2011). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage Publishing.

de Brey, C., Musu, L., McFarland, J., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Diliberti, M., Zhang, A., Branstetter, C., & Wang, X. (2019). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups 2018 (NCES 2019-038). U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/

Espinosa, L., Turk, J., Taylor, M., & Chessman, H. (2019). Race and ethnicity in higher education: A status report. American Council on Education.

Field, K. (2021, July). The missing men. The Chronical of Higher Education, 67(23), 11-14.

Greene-Moton, E., & Minkler, M. (2020). Cultural competence or cultural humility? Moving beyond the debate. Health Promotion Practice, 21(1), 142-145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919884912

Harper, S., & Harris, F. (2010). College men and masculinities: Theory, research, and implications for practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Harris, F., & Wood, J.L. (2013). Student success for Men of Color in community colleges: A review of published literature and research, 1998-2012. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 6(3), 174-185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034224

Hilton, A. A., Wood, J. L., & Lewis, C. W. (2012). Black males in postsecondary education: Examining their experiences in diverse institutional contexts. Information Age Publisher.

Holmes, A. (2020). Researcher positionality - A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research - A new researcher guide. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 8(4), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.34293/education.v8i4.3232

Huerta, A. H., Romero-Morales, M., Dizon, J. P., Salazar, M. E., & Nguyen, J. V. (2021). Empowering men of color in higher education: A focus on psychological, social, and cultural factors. Pullias Center for Higher Education.

Itzigsohn, J., & Brown, K. (2015). Sociology and the theory of double consciousness. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 12(2), 231-248.

Jackson, K., & Bazeley, P. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with Nvivo (3rd ed.). Sage Publishing.

Lee-Bitsoi, L., Gordon, E. T., Harper, S. R., Saenz, V. B., & Teranishi, R. T. (2014). Men of Color in higher education: New foundations for developing models for success. Stylus Publishing.

Mangan, K. (2014). Minority men struggle to achieve at community college. Chronicle of Higher Education, LX (25), A8.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). The condition of education 2020. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2020144

National Center for Education Statistics. (2019a). Fast facts. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_326.20.asp

National Center for Educational Statistics. (2019b). Digest of education statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_303.70.asp

O'Neil, J. M. (2015). Men's gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change. American Psychological Association

Perrakis, A. (2008). Factors promoting academic success among African American and White male community college students. New Directions for Community Colleges, 142 , 15-23.

Platt, C., Holloman, D., & Watson, L. (2015). Boyhood to manhood: Deconstructing Black masculinity through a life span continuum. Peter Lang Publishing.

Postsecondary National Policy Institute. (2021). First-generation students in higher education. https://pnpi.org/first-generation-students/#

Schmidt, P. (2008). Colleges seek key to success of Black men in the classroom. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 54(A1), A23-25.

Seidman, A. (2012). College student retention (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Stout, K. (2021). Reimagining access. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2021/05/26/community-colleges-need-equity-agenda-opinion

Strayhorn, T. L. (2012). College students' sense of belonging. Routledge.

The White House. (2014). My Brother's Keeper. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/my-brothers-keeper#section-about-my-brothers-keeper

Tinto, V. (2012). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89-125. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00346543045001089

Turner, P. (2016). Supporting freshman males during their first-year of college. College Student Journal, 50(1), 86-94.

Wester, S. R. (2008). Male gender role conflict and multiculturalism: Implications for counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 36(2), 294-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286341

Williams, R. A, Lee-Bitsoi, L., & Gordon, E. T. (2014). Men of color in higher education. Stylus Publishing.

Williams, R., & Flores-Ragade, A. (2010). The educational crisis facing young men of color. Diversity and Democracy, 13(3). https://www.achievehartford.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/CollegeBoard-The-Educational-Crisis-Facing-Young-Men-of-Color-January-2010.pdf

*Contact: peturner@nmsu.eduJournal of Postsecondary Student Success, Volume 1, Issue 3