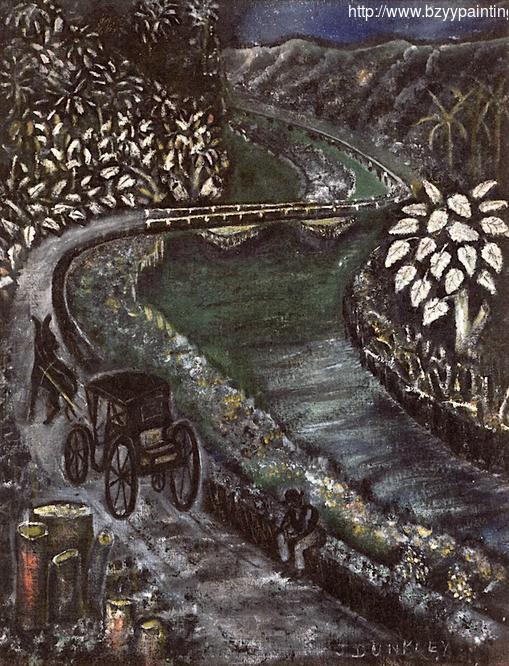

Figure 1. John Dunkley, Feeding the Fishes, mixed media on plywood, 16.75 x 20.125 inches, ca. 1940. ONYX Foundation. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica.

John Dunkley’s Feeding the Fishes (Figure 1) conjures an enticing story of human experience and mystery, writ in sign and symbol. Initially appearing as a quiet reflection of Jamaican life at night, the elements of the composition form a clear set of personal, and at once universal, symbols of contemplation within the disquiet of melancholy. This dark scene of a winding river ravine appears set at dawn. Teeming fish in the stream surround the bait as a hunched woman angles, presumably for the first catch of the day. The woman stands precipitously on the cliff, looking down at the fishes. A prominent branch, resembling an erect penis, cuts across her dangling fishing line. Below, a deep ravine opens into a subtle vaginal form. Dunkley’s landscape imbues sexual overtones within quotidian performances, and, in so doing, reveals a dark underbelly in paradise.1

To decode John Dunkley’s dark and sexual landscape is also to reveal a decolonial message in his broader works. Dunkley humanizes nature through both masculinizing phallic and feminizing yonic symbolism as an emancipatory tactic, thereby reflecting a culturally nuanced relationship between people and landscape. Dunkley subverts the expected in Caribbean painting, especially for foreign consumers. By bringing nature to life, his paintings offer subversive anti-colonial themes, too, waiting for decipherment. This paper will examine Dunkley’s use of erotic imagery, arguing that the painter’s sexual landscapes, through layered poetics and symbolism, ultimately served to challenge every day oppressions in colonial Jamaica.

Both yonic and phallic symbols appear in almost all of Dunkley's paintings, including Spider’s Web (Jerboa) (Figure 2), Mountain Edge (Figure 3), and Going to the Market (Figure 4). Unfortunately, Dunkley left no clues to the erotic imagery’s meaning. This paper thus aims to offer one possible reading of Dunkley’s personal symbolic web, focusing on his humanization of the landscape through sexualized elements. Applying a decolonial lens to Dunkley’s paintings and socio-political interests reveals the phallic symbol as a mode of “remasculating” the Black Jamaican man while the yonic sign, in turn, represents the strength of the island’s mother culture. Placed together, the signs suggest an image of fertility.The rebirth and continuation of the Jamaican peoples.

Dunkley was born in Savanna-la-Mar, a small port town in rural southwest Jamaica, in 1891.2 During the period between 1912 and 1929, Dunkley traveled throughout Central America and the Caribbean. Dunkley moved back to Kingston in 1931, where he married Cassie Fraser, fathered at least four children, and opened up a barbershop on Princess Street in an Afro-Jamaican populated neighborhood in Kingston.3 This one-story wooden building served as his salon, studio, and at times, family home, as the economy declined in Jamaica during the Great Depression. Dunkley began creating work in the 1930s, executing much of his body of work in the 1940s, until his death from cancer in 1947.4 John Dunkley’s artwork was both influential and extraordinary. Despite never rising to financial success, he was well-regarded during and after his lifetime by fellow artists and politicians, including Norman and Edna Manley.5

Dunkley worked and travelled throughout the Caribbean and Central America in the early twentieth century, and he was well acquainted with Pan-African ideas then on the rise throughout the Western hemisphere. Dunkley was particularly interested in the teachings of the Jamaican-born activist Marcus Garvey, who pushed for the unification of the African diaspora with Mother Africa. He was responsible for the formation of a universal Black consciousness.6 This Jamaican national hero was significant in inspiring future movements and forming much of the modern understanding of Pan-Africanism. While Jamaica remained a British colony until 1962, other Caribbean colonies were gaining independence as early as 1804 (in the case of Haiti).7 In Dunkley’s time, the Great Depression created economic hardships across the island. The Jamaican people, too, grew restless and frustrated at being a Crown Colony and advocated for independence over several decades.8 During this unrest, Jamaicans called for their own national identity separate from Great Britain. This rising sense of nationalism resonated with Dunkley.

Dunkley’s artwork reveals his interest in decolonialism – the desire to confront and challenge Western paradigms of tradition and modernity. Many of the hidden symbols in his landscape speak to his Caribbean peers and call for decolonial action. This theme is carried on through Dunkley’s sexualized symbolism. Dunkley’s works, although primarily nature scenes, are highly erotic. Dunkley incorporates both female and male genitalia within the landscape, imbuing nature with life to tell its own story. The concept of bringing the landscape to life has a particular resonance in the Caribbean. For many of Dunkley's Jamaican contemporaries, nature was supernatural.9 Stemming from African beliefs, Jamaicans believed that spirits lived in the forests and that plant life had healing powers.10

The Jamaican living landscape itself may have inspired this sexual imagery within nature. David Boxer, prominent scholar of Jamaican Modernism, proposes that Dunkley was inspired by the famous “Pum Pum Rock,” or “Pym Rock,” at the Rio Cobre, which was on the route to Kingston and well known to Jamaicans.11 The Pum Pum Rock is famous to this day in Jamaica as an explicitly sexual formation, resembling female genitalia. “Pum Pum” is a Jamaican slang term for vagina still today.12 This crevice in the side of a gorge contributed to Dunkley's sexualization of the landscape. Dunkley would have certainly been familiar with this natural topography, not only because it was – and still is – quite notorious in Kingston, but also because he painted a scene of the Rio Cobre, in Flat Bridge (Figure 5), a site only a mile south of Pum Pum Rock.13

Boxer claims that this strange rock formation “occupies a special place in [the Jamaican] spiritual imagination,” especially considering that there was once a phallic rock that stood perpendicular across from Pum Pum rock.14 Although removed in the 1950s, this erect rock illustrated a metaphor of sexual intercourse with the natural world. This coincidental juxtaposition of erotic imagery inspired Dunkley’s sexualizing of the landscape. As Boxer further states: “nature’s metaphors, made so by the imagination of man, Pym Rock, and the phallic rock, . . . became principal triggers for Dunkley, giving rise to his anthropomorphizing of the landscape and a visual encoding of sexual fantasy, and perhaps memory, as well."15

This erotic and energetic rock formation is likely referenced in Dunkley's Feeding the Fishes. This painting depicts a woman bent over a river, fishing, while a large trunk penetrates the foreground of the composition, pointing toward a crevice in the flat rock across the stream. Here, Dunkley created a motif similar to the natural formation of the Pum Pum Rock and its adjacent phallic rock. Dunkley overtly eroticizes and engenders the composition through the natural elements of the landscape.16 By doing so, he creates a commentary on decolonialism.

Colonizers were fascinated with the non-Western Other, and they sexualized indigenous, African, and Asian subjects as means of domination.17 French writer Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, famous for validating racist thought, reflects the colonial perception of the non-Western Other. In his infamous essays, The Moral and Intellectual Diversity of Races and The Inequality of Human Races, Gobineau categorizes different races as being “male” and “female,” claiming that the majority of non-European races were feminine, and thus inferior.18 In this white supremacist pipe dream, the white man establishes the pinnacle of an imagined racial hierarchy through the already established European hierarchy of gender: “just as the white male rules at home, so he also lords it abroad.”19 This system, therefore, feminizes both Black males and females alike. The colonizers emasculate non-Western men, and exploit their bodies for labor. The white man’s call to power strips the Black man of any agency.

Dunkley’s phallic and yonic symbols are more than erotic. They are tools of emancipation. Set amid dark colors and unsettling scenes, Dunkley’s use of sex organs helps disrupts the subservient stereotype of the Caribbean subject. In Feeding the Fishes, a large phallic trunk interrupts the scene, overpowering the feminine symbols in the background. The imposed masculine energy conquers the scene, reclaiming power. Through Dunkley’s composition, the landscape is broken down into fetishized and engendered parts. Dunkley thus uses the colonizer’s own language to reverse the emasculation of the Jamaican populous. As Dunkley asserts the masculine icons in the canvas, he symbolizes a reclamation of power. In Feeding the Fishes, the phallic symbol penetrates the composition, both taking the central focus away from the figure and energizing the scene. In Feeding the Fishes, the penis is prominent. The phallic symbol is incorporated more subtly in the majority of Dunkley’s paintings. For example, in Going to the Market (Figure 4), the phallus is almost hidden beneath the patterned bush on the right, where sits a tiny cluster of branches that resemble Dunkley's familiar phallic motif. In this subtle incorporation of the male genital organ, Dunkley continues to reclaim both his own and, more broadly, Afro-Jamaican masculinity. In doing so, he takes back power by destroying the prevalent hierarchical system of races in relation to gender.

Through the incorporation of the phallic symbol, Dunkley reinforces Jamaican masculinity, and defies the subordinate and passive role appointed Jamaican men by their oppressors. As Dunkley’s phallic symbols are incorporated to reclaim their power, I also argue that the yonic symbol carries an equally emancipatory power in Dunkley’s works. In Jamaica, women are regarded as the backbone of society. Nearly half of all households are matriarchal and many women work while domestically caring for their family.20 Former Prime Minister of Jamaica and cultural essayist, Edward Seaga, noted that “women [are] symbols of achievement in Jamaican folk society … As such, they are more than women or mothers; they are a resource base of cultural identity.”21 Women are especially respected for their fertility, and therefore Dunkley’s repeated representation of female genitalia, as seen in Mountain Edge (Figure 3), carries strong meaning.22

In Decline of the West – an influential text, popular in the Americas in the early twentieth century – Oswalt Spengler claims the formation of culture is rooted in the landscape and symbolizes the landscape as the mother of all culture.23 The symbol of the mother references the origins of culture and life, as he compares the act of birth with the creation of culture “out of its mother-landscape, and the act is repeated by every one of its individual souls throughout its life-course.24 Additionally, the mother-landscape symbol reflects the future, as the cycle of birth reflects a continuum of fertility and life. The idea of the earth-mother is an ancient metaphor for the life-giving resources the land provides. This, along with the status of women and mothers in the Jamaican working-class, strengthens the mother-landscape metaphor used by Dunkley in his work.

Dunkley uses this proto-feminist metaphor as a subversion of colonialism. By painting the landscape as a fertile giver of life, the land is salvaged from colonial destruction. Despite the introduction of new flora and fauna, and the deforestation conducted on the island, Jamaica still thrives. The life cycle continues. Spengler states, “the symbol of the mother-womb [is] the origin of all life.”25 This idea is exemplified in Banana Plantation (Figure 7), as the rabbit hides underground in a burrow. This hollow subterranean home resembles a womb. The rabbit is safe and hidden from the outside dangers and nourished with its fruit. The Jamaican land takes care of its people. They rely on their home for nourishment and protection, even while all around them, colonialism attempts to destroy their home with the revealing setting of a plantation. By referencing the mother in the landscape, Dunkley provides hope for the future of Jamaica. This scene is complete, as a full moon, a symbol of fertility in Jamaican folklore, watches over the Banana Plantation.26

Returning to Dunkley’s Feeding the Fishes, the theme of fertility continues. In this painting, a penile tree trunk points towards a vaginal rock formation. The land itself appears engaged in sexual activity; however, this act takes on a different meaning when further examined. Through the combination of both male and female energy, themes of natural procreation emerge, thus painting the Jamaican landscape as literally fruitful and fertile. A metaphor for reproduction emerges within this painting. The landscape is not sexualized solely for erotic purposes, but also for reproductive purposes, thereby reintroducing the theme of fertility.

In this artwork, behind these personified objects, stands a woman, who leans over the edge of the cliff. She is attempting to fish but, presumably, the attempt is futile, and she is merely "feeding the fishes." Dunkley uses wordplay by referencing the outmoded, colloquial idiom "feeding the fishes," which in Jamaica refers to morning sickness.27 Dunkley rarely depicts figures within his landscape paintings, however he chooses to symbolize the beginnings of new life through this expectant mother. With this knowledge, not only does the figure of the hunched over woman take on a new meaning, but also the environment around her appears to be given new purpose. As the rocky ground around her is mostly barren, new vegetation sprouts all around the impregnated woman. The only plant life in the painting is around the woman’s feet and beneath the penis-tree trunk. Thus, these elements that may have at once appeared merely erotic are now the bearers of new life.

Dunkley’s Feeding the Fishes is one of the most sexually explicit and engendered of Dunkley’s paintings. The background suggests a subtle femininity through the crevice in the rock and the implied pregnancy of the figure. The theme of fertility is clear through the sexually explicit phallic tree and yonic rock formation, the plant life emerging from the barren land, and the title of the painting that directly refers to reproduction. This fertility symbolizes the future. As procreation creates generations to come and crops to nourish them, the future of Jamaica is present in this painting. The phallic rock interrupts this apparent metaphor for the future and fertility of the island to reclaim their power and assert their dominance once more.

Through his sexualized symbolic code, Dunkley makes the components of his paintings readable, able to convey meaning without verbal language, thus creating a more powerful language with the capacity to say more than mere words. Dunkley’s use of the phallic and yonic symbols similarly exemplifies commentary on decolonialism, one that embodies the strength and persistence of the feminine, reclaims power through masculinity, and reflects the tenacity of the Jamaican peoples through the metaphor of reproduction and rebirth.

Figure 1. John Dunkley, Feeding the Fishes, mixed media on plywood, 16.75 x 20.125 inches, ca. 1940. ONYX Foundation. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica.

Figure 2. John Dunkley, Spider’s Web (Jerboa), also exhibited under the titles Jerboa and Spider’s Web, mixed media on plywood, 28 x 14 inches, n.d., National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica.

Figure 3. John Dunkley, Mountain Edge, mixed media on plywood, 20.875 x 16.09 inches, ca. 1940, ONYX Foundation. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica.

Figure 4. John Dunkley, Going to the Market mixed media on plywood, 34.75 x 14.875 inches, ca. 1943, ONYX Foundation. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica.

Figure 5. John Dunkley, Flat Bridge, mixed media on canvas, 20.625 x 16.5 inches, ca. 1935, The Michael Campbell Collection. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica.

Figure 6. John Dunkley, Banana Plantation, mixed media on plywood, 29.125 x 17.625 inches, ca. 1945, National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston, gift of Cassie Dunkley. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica.

A special thanks to the UMKC Women’s Council for providing me with the grant that allowed me to visit Kingston, Jamaica, to experience John Dunkley’s artwork firsthand and conduct valuable research on this project. And a special thanks to the National Gallery of Jamaica, particularly Dwayne Lyttle, Monique Barnett-Davidson, and Shawna-Lee Tai, for all their help with research, interviews, images, and support. Additionally, thank you to Dr. Joseph Hartman and the UMKC staff for their guidance and encouragement throughout my studies.

David Ebony, “Caribbean Twilight,” Magazine Antiques 185, no. 4 (August 7, 2018): 88.

Cassie Dunkley, “The Life of John Dunkley,” reprinted in Jamaica Journal 11, no. 1–2 (August 1977): 82. Unfortunately, not much is known about John Dunkley, as he left no writing and only a handful of newspaper blurbs mention his name. The majority of our knowledge of Dunkley’s life comes from a short text his wife wrote for The Institute of Jamaica’s posthumous “Memorial Anniversary Exhibition of the late John Dunkley, Artist and Sculptor” in 1948.

David Boxer, “The Life and Art of John Dunkley,” in John Dunkley: Neither Day nor Night, (Miami, FL: Prestel, 2017), 19-22.

Dunkley, “The Life of John Dunkley,” 82.

Judith Stein, The World of Marcus Garvey: Race and Class in Modern Society (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986), 248.

“The Countdown to Independence,” Jamaica Journal 15, no. 46 (n.d.): 21–23.

“The Countdown to Independence,” 21-23.

John Rashford, “Plants, Spirits, and the Meaning of ‘John’ in Jamaica,” Jamaica Journal 17, no. 2 (May 1984): 68.

Barry Chevannes, Rastafari: Roots and IdeologyUtopianism and Communitarianism, (Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse University Press, 1994) 26-7.

Boxer, “The Life and Art of John Dunkley,” 29.

“Pum Pum | Patois Definition on Jamaican Patwah,” Jamaican Patwah, accessed March 16, 2019, http://jamaicanpatwah.com/term/pum-pum/1065.

“The Pum Pum Rock,” Jamaica in a Thousand Words (blog), May 12, 2016,https://jamaicainathousand

words.wordpress.com/2016/05/12/the-pum-pum-rock/.

Boxer, “The Life and Art of John Dunkley,” 29. In this section of Neither Day nor Night, Boxer provides an in-depth psychoanalysis of the phallic symbol, focusing on the possible sexual frustration and fear of impotency of Dunkley.

Ibid., 29.

Ibid., 29.

Robert Young, Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture, and Race (London; New York: Routledge, 1995), 172.

Arthur Gobineau, The Inequality of Human Races (London : William Heinemann, 1915), 92-3.

Young, Colonial Desire, 104.

Edward Seaga, “The Folk Roots of Jamaican Cultural Identity,” Caribbean Quarterly 51, no. 2 (2005): 90.

Seaga, “The Folk Roots of Jamaican Cultural Identity,” 90.

Chevannes, Rastafari: Roots and Ideology ,28.

Ben A. Heller, “Landscape, Femininity, and Caribbean Discourse,” MLN 111, no. 2 (March 1, 1996): 393-4.

Oswald Spengler and Charles Francis Atkinson, The Decline of the West (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1926) 172.

Spengler and Atkinson, The Decline of the West, 82.

Chevannes, Rastafari: Roots and Ideology ,26.

Boxer, “The Life and Art of John Dunkley,” 29.