Figure 1. Drew Bacon, (installation detail) Life, 2017, Silver Street Studios, Houston, TX. Photo credit: Drew Bacon.

Life began for me at a point different from where it began for the visitor in front of me. The work started at yet another point for someone arriving later than I did. The footage may have already begun again for some early arrivals to the exhibition. That evening, Life (2017) began again for all of us, probably more than once. Drew Bacon’s most recent animation started for viewers as it was constantly refreshed and reinvigorated through the sporadic recognition of his images. When I first witnessed Bacon’s Life, I thought the footage ran continuously forward, taking new material for its own figuration as it swept through a limitless digital inventory.

I came to realize that the images flitting and shuffling across the wall were not digitized before Bacon’s endeavors. Acrylic paint and strategic tears accent the pages, the units of the animation, to draw our attention to the stuff of which the artist’s latest projection is composed: thousands of photographs made of thousands of pages and images from LIFE magazine’s golden era during the fraught 1960s up until 1972. Bacon’s marks and arrangement of the material render LIFE magazine’s vast amounts of reporting indiscernible, closing off any possibility of a complete reading. The artist highlights the tension between the amount of information presented and the amount of information left legible - a conflict repeated throughout contemporary society, especially as we digitize and publish our records online.

Bacon cut pages from LIFE, painted on them in patterns, and documented his accents with a digital camera - photographing each mark stroke-by-stroke. He then sequenced and animated the modification of the documents into a continuous loop. After editing the video with meticulous attention to the pixels through which the images are rendered, Bacon broadcasts his work across several yards of wall space, often using more than one projector (Figure 1). In the gallery, the projection occupies a blank wall, enveloping viewers as they move in and out of the projectors’ light.

The following critique addresses the theatrical response of spectators to both projection and the animation it presents. Despite its utter ubiquity, the essay “Art and Objecthood” by Michael Fried provides lasting insight into the efficacy of projection as artists such as Bacon search vast source materials for trends in imagery from our nation’s collective memory and ideology. It is possible to deploy projected light on large scales, as the instruments can replicate animation in perfect loops without diminishment in resolution. Thus, the medium of projected light exerts itself as a natural choice for literalizing our subjective, theatrical interaction with the records through which our histories are recorded.

Bacon’s characteristic preparation of documents is not exclusive to LIFE magazine, nor is this most recent work the first time he has deconstructed the authority of published pages to create his animations. His technique has found purchase on the encyclopedia, the dictionary, recent issues of the New York Times, and now, the pages of this iconic publication. His choice of LIFE magazine as the source material for this most recent work is eerily intimate - even seen briefly in the animation, the pages still retain the personal ethos characteristic of the publication. At the height of its distribution in the early 1970s before changing to monthly circulation, thirteen million issues of LIFE were home-delivered each week. Often, the issues of LIFE were “passed along” to four or five individuals after the initial subscriber read the magazine, reaching a secondary audience of more than forty million.1 The magazine purported to consolidate a world of information into one source, where news of the Civil Rights Movement, the War in Southeast Asia, the Space Race, and other national endeavors were juxtaposed with sleek advertising complicit in an insulated American dream.

Bacon’s preparation of Life took place over months in which he rifled through issues, cut out and set aside interesting pages, documented their transformation, then set them aside again - laden with paint, warped, and isolated. Occasionally, he has admitted, a day in the studio was spent engrossed in reading the un-altered magazine, and no marks, cuts, or tears were made.2 Bacon begins his mark-making by casting accents on pages in a way that exemplifies the “message” of the whole. This involves painting forms that reverberate the visual qualities of the folio: vertical brush strokes to mimic a wood fence featured on one page, a spiral composed of line segments painted over the smug face of a war criminal on another. As a result, the audience gleans a sense of the content of the page without reading it, though the synthesis presented is not an objective reading of the facts. Rather, the markings are one reader’s (Bacon’s) own resonance with the information.

It would require a lifetime of work to parse out and read Bacon’s images as they have been arranged in this sequence. The original magazines are no longer entirely legible either. Even if a viewer could stop Life and take from it one of the pages on the wall without paint obscuring its contents, the document would still be far from its rightful context in the curated periodical. The interface of the projection consolidates years of archived material, though in doing so eliminates the chronology and editorialization that structured LIFE as a conduit for the world’s news.

Bacon’s mark-making is an eclipse of the coherent message of the page; his arrangement is a blurring of the narrative constructed by the original issue of LIFE. If the editors of LIFE succeeded in disguising their reinforcement of mainstream American values behind the veil of objective reporting, that guise is betrayed by Bacon’s projection of the materials. Bacon’s presentation reinforces the human and personal quivering just below the surface of LIFE - recognition, memory, ideology. In his own estimation, Bacon has composed his story of life: how we come to be born, live, work, and eventually return to dust.3 Watching Bacon’s dissolution of the myth of objectivity into the reality of subjectivity on such a large scale, the audience comes to feel what it is like to live life at this moment.

In a gallery, the animation leads a life of its own, drawing viewers back to it continuously throughout the night to see where it has led since they last glimpsed it. The animation is a unified, though not a “Specific Object,” as Michael Fried defines the “literalist” sculpture of the late 1960s in his well-known essay of the time.4 For Fried, the object reduces to its shape; for Bacon, it could be said that the object becomes the forms that rise to the surface and repeat throughout the course of LIFE’s publication.

Unlike the literalist sculpture of Robert Morris or Donald Judd, Bacon’s animation poses no physical inhibition to being navigated. Spectators make themselves at home in the projection’s glow, chatting and drinking, not having to raise their voice in Life’s presence. As onlookers move toward and away from the wall to get a closer look at a cover from LIFE or one of Bacon’s marks, the light shifts and softly falls on their bodies.

Discussing the work as it is “happening” is good for conversation. The vintage material inspires conversation and incites questions. Patrons cluster together in groups to reveal and brag about what they recognize in the sequence, or to ask about the identity of a product featured in a truncated ad. As soon as an answer to any number of questions is formulated, a dozen more rise to the surface of the churning body of information.

Finding familiarity in Bacon’s animation is almost as natural a process as watching it. In fact, to watch Bacon’s work is to latch on to what is familiar, even if the image is on the wall for a fraction of a second. The recognizable tidbits scattered throughout the work (different for each individual who chances upon it) are what keep spectators interested and expectant. If Bacon had simply sequenced every page from a certain range of issues of LIFE magazine, we as viewers would be inclined to do what Bacon has already done with his projection: break down the whole of LIFE into what resonates with the viewers’ experience and memory. Bacon’s aestheticized presentation across the gallery wall highlights something familiar and appealing for a moment, all the time that is needed to recognize the image from across the room. These units (the pages and images from the magazine) are linked together in the narrative of Bacon’s animation and are the objects of our interaction.

Even as we watch Bacon’s animation, memories of earlier parts of the footage become operative as they reappear in the sequence again and again. Maybe in waiting for this image to return, we recognize another. And another. Life expands when we recognize an image to anchor our looking. It begins many times throughout the animation, as I trust it is impossible to recognize only one out of the thousands of visual signs presented. I cannot say what another viewer may recognize - this is an individual experience mandating access to the memories of a vivid past.

To look more critically at the effects of these techniques in Drew Bacon’s Life, I have paused the work at what I feel to be a pivotal image, one crucial for our understanding of Bacon’s methods, though perhaps most central to my own understanding of the effects of Bacon’s work. Fried criticized literalist work for its indistinct relationship to the parts of its composition; Bacon has related every object within his arrangement to each other simply by way of presenting the pages of LIFE magazine through the format of projection. As a result, we are able to recognize distinctly subjective qualities of the publication as we might recognize “gestalt” forms arranged in a gallery.5

One image now recognizable to me is that of former Army Lieutenant William Laws Calley. After panning over his arm, and before his face is obscured with a centrally-focused spiral of line segments, the man is visible. He is reclined and even relaxed, his head highlighted against the foreground of his soft blue tracksuit. To his right appears a painted oblong resembling the outline of a seed or a heart. To his left, and in between the outlines, appear exclamation points painted over images of young boys playing with toy rifles.

In March of 1968, United States Army infantrymen destroyed the village of My Lai, located in the central highlands Vietnam. Operating on false information, two platoons (one of them Calley’s) proceeded to infiltrate the reportedly “hostile” village. Despite establishing that those present in the village were civilians, and not North Vietnamese Army or VietCong combatants, the soldiers proceeded to carry out one of the largest and most infamous massacres in our military history. Acting under orders from Calley, United States servicemen opened fire upon hundreds of peaceful villagers, raping and torturing some before ending their lives.6

Calley was court-martialed and tried between the years 1969 and 1970 for his actions at My Lai. In 1971, the Lieutenant was convicted for the premeditated murder of twenty-two out of the estimated five-hundred dead Vietnamese civilians at My Lai. He was sentenced to life in prison and to hard labor at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, before this sentence was altered one day later by President Richard Nixon himself. Nixon ordered that Calley instead be transferred and confined to house arrest in Fort Benning, Georgia, where the Lieutenant served only three and one-half years of his sentence.7

It was during his house arrest that Calley, who was twenty-six years old at the time, was interviewed and photographed for LIFE magazine (Figure 2). The article and Calley’s image were published at a time when the American public and many politicians believed that the Lieutenant was unjustly blamed for the events at My Lai. Among supporters of the war, the objection that a soldier could not be held responsible for the consequences of “following orders” ran rampant. Calley remained a recognizable figure in the years following the massacre at My Lai. The reporting surrounding his conviction and his sentence further galvanized the public’s attention toward him and the supposed truth behind all being fair in war. Even as the nation protested the war’s expansion deeper into Southeast Asia, LIFE magazine remained at the forefront of the war’s justification.

Today, perhaps out of intentional furtiveness, Calley’s visage is nearly indiscernible amid the plethora of photos and articles presented in Drew Bacon’s Life. I myself did not recognize him until Bacon’s father pointed him out at Life’s opening, asking me, “no one in your generation knows who William Calley is, do they?”

I recognized the name, and because of the name, I recognized his face. I formed a substantiated connection with the work. Incidentally, I learned about Calley and his actions years before from my own father, who at age seventeen enlisted in the Marine Corps and was deployed in the central highlands of South Vietnam, not far from, and just four months after Calley’s massacre. News of the killings was obscured for months after the crime, though eventually the facts could not be contained. Perhaps after his tour of duty, and while serving as a drill-sergeant at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, my father came to know what had been done on that day by American servicemen not dissimilar from himself or the ones he was now responsible for training.

What I remember most clearly about my father’s brief comments on William Calley was that he believed no one is capable of reconstructing and accurately evaluating the significance of that terrible day: that objective judgment of the murders was impossible, no matter how heinous they were. (I believe his words were something to the effect of, “If you’re mad about what Calley did, you’re not thinking hard enough about what we did to Vietnam.”) What I understood was that any attempt at reconstructing the events of that day or the days after would be mere projection.

Whether Bacon intended Calley’s presence in the animation to act in this way, the inclusion of his image brings to the forefront the kind of uncertainty about fact and embellishment that is repeated throughout Bacon’s work and throughout LIFE magazine. The recognition of Calley’s image begins an internal debate on the nature of crime and atrocity, and sets into motion the distraught contemplation of what is just and right. I am left with questions on the uncertainty of regulating the events, perhaps all of them crimes, that transpire among young boys during war. It is possible that this reflection is exclusive to my reading of Bacon’s Life, though the large scale and repetitive imagery of the projection allow for constantly refreshed consideration from all viewers.

Outside of my vigorously personal connection to it, Calley’s image is important for another reason: it is one of the few images in the work that is abstracted by “zooming” close to it. First, Calley’s arm is depicted as a combination of nondescript geometric forms; to the right a matador seems to shout as Bacon paints and animates red triangular forms emanating from his mouth. As the video continues to play, his entire upper body comes into view and is eventually eclipsed by the red and white spiral abutted by images of falling bombs. From the first depiction of Calley’s body, his significance is abstract, regardless of how much one viewer may know about him, or how quickly they are able to recognize him out of the distortion.

Bacon’s work, composed out of fragments of characteristically American journalism, elicits the intensely subjective responses the editors of LIFE might have worked to suppress. The medium of projected light is particularly suited for the magnification of this information. Bacon is able to animate his altered pages from LIFE at life-size, aggrandizing and making literal our personal relationship to the periodical. The word projection itself bears many associations. A projection is an image presented on a surface; it is also defined as a mental image viewed as reality. As a psychological term, projection describes the transfer of our unconscious desires and fears onto the perceived characteristics of our peers.

All of these denotations are centered on projection’s capacity for illusion. By figuring an image through a projection, the operator is able to subject the image to modification depending on the circumstances of the environment in which it is displayed. Projection’s representational, and therefore illusionistic, faculties are born out of its overlapping reality. In the case of Drew Bacon’s Life, the projection occupies the gallery wall, and occasionally the skin of passersby (Figure 3). The artist can scale his images to more directly confront, and incorporate, the viewer. As the images and articles from LIFE magazine are projected into the audience’s space, Bacon’s animating - his literal “making alive” the material - facilitates a subjective confrontation of presence, as though the pages of LIFE magazine were standing in the room with us.

Projected animation subverts Fried’s critique that an object confronting its viewer physically (as the geometric volumes of Robert Morris did) is not entirely self-contained. In Bacon’s animation, the disparate objects of his arrangement are the pages and images from LIFE magazine that he has selected. His repeating sequence ties the pages together in a new volume, and as they are presented at such a large scale, viewers are confronted with their own memories and subjective response more urgently than when reading through a single issue. LIFE magazine’s figuration had always been performative to a receptive audience of millions during the height of its publication. Rather than diminishing the impact of Bacon’s artistic enterprise, the theatricality witnessed in the glow of Life’s projection is the crux of the project.8

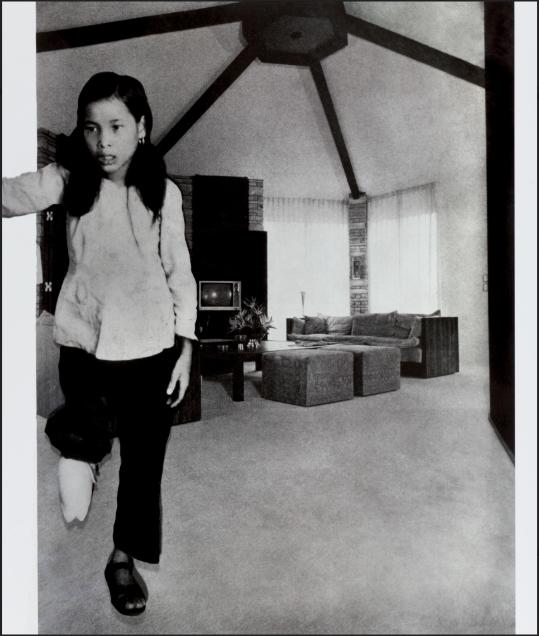

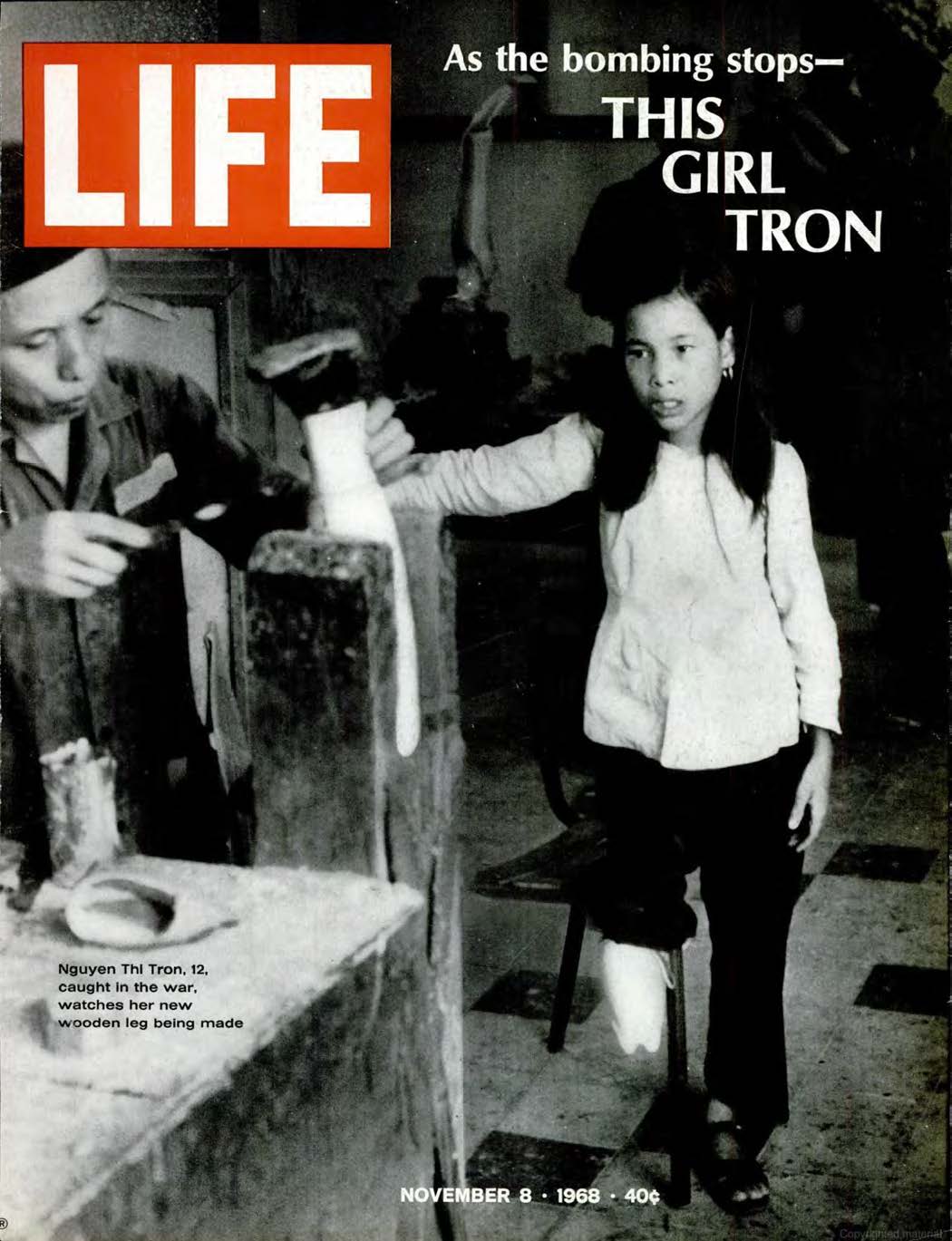

LIFE magazine figures prominently in a past undertaking along the literalist and confrontational lines identified by Fried. From 1967 through 1972, Martha Rosler cut images from LIFE magazine and arranged them within interior scenes from the aspirational magazine House Beautiful. The resulting photomontages were distributed to other women at anti-war demonstrations, providing Rosler’s audience with a collision of memories and desires. One such photomontage, Tron (Amputee) (Figure 4) combines the image of a wounded Vietnamese girl, the eponymous Tron, with a pristine American interior.

The original cover of LIFE magazine Rosler used as the source for her work features the caption, “Nguyen Thi Tron, 12, caught in the war, watches her new wooden leg be made” (Figure 5). By projecting Tron into the space of the American living-room, Rosler makes literal the country’s relationship to the media flowing out of our ongoing conflict in Southeast Asia. The editor writing on the cover of LIFE only makes mention of “the war,” leaving it to the readers’ imagination which conflict could be the one that took Tron’s leg. Printed within the issue are all of the advertisements and editorials one would expect from LIFE magazine’s reporting. Perhaps some of the images and pages have been included in Bacon’s animation.

Just as Rosler’s photomontages compress vast distances between “the war” and where its images were consumed (journalists nicknamed the war in Vietnam “the living room war”) Bacon’s animations, and the drawings of which they are composed, heighten consciousness. They are constructed out of the thinly-veiled propaganda contained in LIFE magazine, now subjected to the artist’s touch. Whether it is living and carrying out its figuration in a gallery in Houston, or transmitted and projected simultaneously across the state, Bacon’s altered images compress the distance between objectivity and subjectivity - they are new information derived from the old. Bacon’s Life is the new story - the only story - your story, formulated at the moment of its recognition, time and time again.

Life becomes relegated to mythology as accounts of the work are disseminated. The facts contained within it are as infinitely indistinguishable as the number of individuals capable of describing what they see in Bacon’s projection. The artist has set into motion something that will never stop, a phenomenon that is no longer his to control. Since its official unveiling in October of 2017, Life has started again an inconceivable number of times. Viewers have taken bits of information from Bacon’s presentation away with them into their homes and into conversation for the next lifetime. You could live with Bacon’s work for years, as I have been fortunate to do, and never realistically decipher its messages. Memory is all that is yours to keep; I suspect that everyone who has watched Bacon’s Life feels a connection, and remembers it.

In this way, the artist has literalized the process through which we can appropriate objective information - pick it out, frame it, and highlight what we recognize – be it literalist sculptural forms or images placed in our midst. In the time you watch Life, its lively presence elicits and interpolates the audience’s past, memories, biases, and beliefs. There is a direct relationship, seen prominently in Bacon’s work, though featured prominently in our own psychology, between a world of fact and its instantaneous reaction with our own, very small, lived experience.

We can extend Life’s impact just as we extend any fleeting phenomenon – by discussing it, recognizing it, communicating it across our network of acquaintances – by remembering it as we do anything we see. These undertakings make the illegible work more tangible, though no one could ever determine the truth or fiction within Life’s composition and influence. Memory, falsehoods, fragments, and (only occasionally) truth – this is life as we know it best.

Figure 1. Drew Bacon, (installation detail) Life, 2017, Silver Street Studios, Houston, TX. Photo credit: Drew Bacon.

Figure 2. Drew Bacon, details from Life, 2017, Silver Street Studios, Houston, TX. Photo credit: Drew Bacon.

Figure 3. Drew Bacon, (installation detail) Life, 2017, Silver Street Studios, Houston, TX. Photo credit: John H.P. Semlitsch.

Figure 4. Martha Rosler, Tron (Amputee) from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, c. 1967-1972, pigmented inkjet print (photomontage), printed 2011, Collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Figure 5. Larry Burrows, cover of LIFE magazine, November 8, 1968.

Erika Doss, “Introduction: Looking at Life: Rethinking America’s Favorite Magazine, 1936-1972,” in Looking at Life Magazine, ed. Erika Doss (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), 1.

Drew Bacon. Interview by John H.P. Semlitsch. Houston, TX. October 21, 2017.

Ibid.

Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” in Art in Theory 1900-2000, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 837. Fried notes that part-by-part composition of sculpture is anathema to the immediacy of literalist forms. Bacon subverts this anxiety by binding his disparate objects into the whole of an animation, which occupies three-dimensional space with light, rather than solid matter.

Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” 837. Fried conceptualizes gestalt as Morris does: The “constant, known shape” which Bacon deploys is the recognizable imagery and reporting from the iconic LIFE magazine. Included is our reaction to it, an aspect of our ideology conditioned and reinforced by “objective” presentation of news in diverse publications. Morris’s sculpture may afford the viewer the chance for insight into their body’s relationship to literalist forms in the gallery. Bacon’s projection enlarges the content of LIFE magazine and confronts us with our own subjective responses.

Seymour M. Hersh, “Coverup - I,” New Yorker, January 22, 1972.

Douglas Linder and Andrew Morgan, “The My Lai Massacre Trial,” accessed June 11, 2019, https://www.jurist.org/archives/famoustrials/the-my-lai-massacre-trial/

See Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” 839. The author states, “the experience of literalist art is of an object in a situation - one that, virtually by definition, includes the beholder.” While Bacon’s Life is not minimalist, per se, its effects are immediate as viewers are confronted with large-scale selections from a periodical that had such an intense impact on our cultural memory. By creating a gestalt form out of years of reporting, LIFE magazine’s complicity with American ego-centrism becomes painfully clear.